Tailwind CSS has taken the frontend world by storm—7.5 million weekly downloads, adoption by GitHub and Shopify, evangelists proclaiming it revolutionary. But strip away the marketing, and you’re left with something uncomfortable: it’s essentially inline styles with a build step. We spent 15 years learning to separate structure from presentation. Now we’re backtracking and calling it innovation.

Why Developers Love It (And That’s the Problem)

To be fair, Tailwind solves real pain points. Naming CSS classes is exhausting—what do you call that wrapper div? Design systems drift without enforcement. Writing traditional CSS means constant context switching between files. These are legitimate problems that plague frontend teams.

Tailwind’s pitch is seductive: rapid prototyping, built-in design constraints, no naming fatigue. You write className="flex items-center p-4 bg-blue-500" and you’re done. Ship features faster. Maintain consistency automatically. What’s not to love?

Here’s what: you’re solving organizational problems with technical band-aids. If your team can’t write disciplined CSS, Tailwind won’t fix that—it just hides the symptom. If naming is hard, your component architecture needs work, not a utility class framework. If design drift happens, you have a process problem, not a technology problem.

It’s Inline Styles. Full Stop.

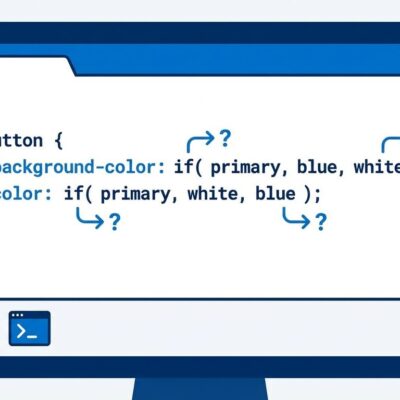

Let’s address the elephant. Compare these approaches:

<!-- Tailwind approach --> <div class="p-4 bg-white rounded-lg shadow-md"> <h2 class="text-xl font-bold">Title</h2> </div> <!-- Inline styles --> <div style="padding: 1rem; background: white; border-radius: 0.5rem;"> <h2 style="font-size: 1.25rem; font-weight: bold;">Title</h2> </div>Tailwind advocates will object: “But we get responsive breakpoints, hover states, and design token constraints!” True. Those are improvements over raw inline styles. However, they don’t change the fundamental architecture: you’re putting styling directly in your HTML. Whether it’s style="padding: 1rem" or class="p-4", you’re coupling presentation to structure.

The separation of concerns isn’t academic pedantry—it’s learned wisdom. Semantic HTML with separated styles means maintainable codebases, accessible interfaces, and readable markup. Tailwind trades all of that for development speed. That’s a terrible bargain.

The Hidden Costs Nobody Mentions

Your HTML becomes soup. Real Tailwind components look like this:

<button class="inline-flex items-center px-4 py-2 bg-blue-600 hover:bg-blue-700 text-white font-semibold rounded-lg shadow-md hover:shadow-lg transition duration-150 focus:outline-none focus:ring-2 focus:ring-blue-500"> Click Me </button>Try code-reviewing that. Try explaining to a designer what focus:ring-2 does. Try onboarding junior developers who need to memorize hundreds of utility class names. Your HTML shouldn’t require a decoder ring.

Moreover, there’s maintainability. Change a design token? Update hundreds of files manually. Need custom styling? Fight the framework or use @apply, which defeats Tailwind’s entire purpose. And accessibility suffers—utility classes convey zero semantic meaning. Screen readers don’t care that your div has class="flex items-center".

You also still need CSS knowledge. Tailwind doesn’t eliminate complexity—it just moves it into your HTML and gives it different syntax. When the framework can’t handle your design, you’re stuck.

Popular Doesn’t Mean Good

The tech industry has a short memory. jQuery dominated for a decade—now it’s legacy debt. CoffeeScript was “the future of JavaScript”—now it’s a footnote. MySpace was more popular than Facebook, until it wasn’t.

Tailwind’s popularity doesn’t validate its approach. Rather, it reveals our collective struggle with CSS at scale and our willingness to accept solutions that treat symptoms instead of causes. Calling something “utility-first” doesn’t make it architecturally sound. It’s still inline styles dressed up in better marketing.

What Actually Works

Better alternatives exist—ones that maintain separation of concerns without sacrificing speed or consistency.

CSS Modules give you true scoping with semantic class names. Your HTML stays clean: <button className={styles.primaryButton}>. Your styles live in separate files where they belong. Similar to how we’ve handled architecture decisions in other contexts, the separation pays dividends at scale.

Design tokens with CSS custom properties enforce consistency without build-step complexity. Define your spacing and colors once, reference them everywhere, maintain semantic CSS.

CSS-in-JS solutions like Styled Components provide component scoping with better developer experience than Tailwind for dynamic styles.

Even semantic BEM, for all its verbosity, keeps your HTML readable and meaningful. You don’t have to choose between development speed and architectural integrity.

We Can Do Better

Tailwind isn’t evil—it’s a pragmatic response to real problems. But pragmatism shouldn’t mean abandoning decades of web development wisdom. The separation of concerns wasn’t arbitrary; we learned it through pain.

If your team ships faster with Tailwind, ask why. Is it solving CSS complexity, or masking organizational dysfunction? Are you building better architecture, or accumulating technical debt with utility class soup? Like we’ve seen with other popular tools that add complexity, sometimes the industry needs to question adoption trends.

The emperor has no clothes. Tailwind is inline styles with a build step and better marketing. We can acknowledge the problems it solves while recognizing it’s not the solution—it’s a regression dressed as innovation.

There are better ways. Use them.