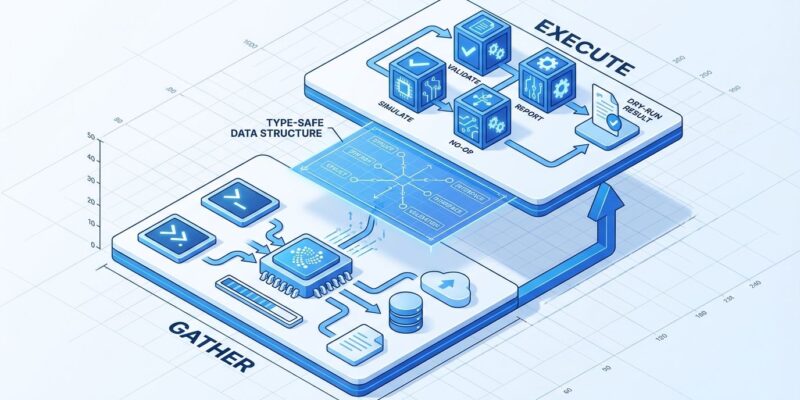

The –dry-run flag prevents production disasters, but most developers implement it wrong. When your dry-run preview says “will delete 5 files” but execution deletes 8, you have a synchronization problem that’s worse than no dry-run at all. The common approach—scattering if dry_run conditionals throughout code—creates maintenance debt that inevitably drifts from actual execution logic. G-Research’s engineering team published a better pattern that treats dry-run as an architectural principle, not an afterthought. Their solution separates code into a “gather” phase that produces strongly-typed instructions, and an “execute” phase that consumes them. The compiler enforces synchronization, making drift impossible.

The Problem: Code Path Divergence

Most developers add dry-run support by sprinkling boolean checks everywhere: if not dry_run: delete_file(path). This creates what G-Research’s Patrick Stevens calls “if dry-run / else soup”—scattered conditional logic that easily drifts during refactoring. When the execution path changes, developers forget to update the dry-run preview. Users trust what they see, then get surprised when execution behaves differently.

PowerShell demonstrates this failure mode in the wild. Functions can declare SupportsShouldProcess to enable the -WhatIf parameter, but if developers don’t wrap every write operation in ShouldProcess checks, some operations still execute during dry-run. Users think they’re protected. They’re not. False dry-run output creates misplaced confidence that leads to production incidents.

The AWS DynamoDB disruption in October 2025 illustrates the cost of this problem. Automation applied an outdated DNS configuration after a new one had already been deployed. The time gap between checking the current plan and applying changes led to deletion of wrong IP addresses. Time-of-check-time-of-use (TOCTOU) races exist in all dry-run implementations, but code path divergence makes them worse.

The Solution: Gather/Execute Architecture

G-Research’s pattern solves synchronization through architecture, not discipline. Separate code into two interdependent functions: gather converts input into strongly-typed instructions, and execute consumes those instructions. The key insight: use dry-run code path as input to execution code path. They’re not separate branches—they’re sequential stages in a pipeline.

In F#, the pattern looks like this:

type ProgramInstructions = { FilesToDelete: string list }

let gather (pattern: string) : ProgramInstructions =

let files = Directory.GetFiles(".", pattern)

printfn "Would delete: %A" files

{ FilesToDelete = files |> Array.toList }

let execute (instructions: ProgramInstructions) : unit =

instructions.FilesToDelete |> List.iter File.Delete

printfn "Deleted %d files" instructions.FilesToDelete.LengthThe execute function is physically incapable of accessing anything not in ProgramInstructions. This isn’t a coding convention—it’s compiler-enforced architecture. If the gather phase changes, the execute phase won’t compile until updated. Drift causes compilation failure, not runtime bugs. This architectural discipline delivers three benefits: the type system prevents synchronization bugs, you can test gathering and execution independently, and the pattern naturally produces reusable library components.

Type-driven development isn’t exclusive to functional programming. TypeScript, Rust, and even Go interfaces can enforce this separation. The principle is language-agnostic: make dry-run output into a first-class data structure that execution consumes.

How Production Tools Implement This

Terraform demonstrates the gather/execute pattern at scale. The terraform plan command generates an explicit execution plan by comparing desired state (configuration files) with current state (state file plus real infrastructure). You can save plans to files (terraform plan -out=tfplan) for team review. The terraform apply command consumes that locked plan, guaranteeing nothing slips in between preview and execution. This two-command model is now considered the gold standard for infrastructure-as-code tools.

PowerShell takes a different approach with its -WhatIf parameter, standard across cmdlets that modify state. The implementation uses ShouldProcess checks around write operations. You can even set $WhatIfPreference = $true to make all operations dry-run by default, requiring -WhatIf:$false to actually execute. This inverted default is safer for administrative tools where mistakes are expensive.

Daily-use tools demonstrate simpler implementations. The git clean command requires the -n flag before permanent file deletion—Atlassian’s tutorial explicitly states “it is a best practice to always first perform a dry run.” Similarly, rsync --dry-run becomes critical with the --delete flag, which can wipe entire directories if source and destination are swapped. These tools prove dry-run doesn’t require complex architecture for simple operations.

The Limitations: TOCTOU and Sequential Dependencies

Dry-run workflows can’t escape Time-of-Check-Time-of-Use (TOCTOU) race conditions. State changes between dry-run (check) and execution (use), especially in distributed systems. Your dry-run might show “will delete 5 files” but execution finds 8 because another process created 3 more in the meantime. Accept this as reality. Dry-run shows intended actions, not guaranteed outcomes.

Sequential dependencies create another challenge. If Step 3 depends on the output of Step 2, dry-run can’t accurately preview Step 3 without executing Step 2. Tools handle this differently: some simulate dependent steps, others show only first-order effects, some accept that complete preview is impossible. Terraform’s plan can’t catch every apply failure—API rate limits, permission changes, or state modifications can still cause execution to diverge from the plan.

The Hacker News discussion around this topic (255 points, 142 comments) shows community consensus: “You can’t eliminate TOCTOU completely, but you can minimize the window and add runtime validation.” The gather/execute pattern doesn’t solve TOCTOU, but it does solve code path divergence. Fix what’s fixable through design, accept what’s inherent to distributed systems.

When to Add Dry-Run to Your Tool

Implement dry-run for destructive operations (deletion, updates), expensive operations (cloud resources), and anything affecting production systems. File deletion tools need it—permanent deletion has no undo. Database migration scripts need it—production data is at risk. Infrastructure-as-code needs it—mistakes cost money. Deployment automation needs it—production outages cost more.

Skip dry-run for read-only operations, trivially reversible actions, and pure calculations. The git commit command doesn’t need dry-run because commits are local and easily undone with git reset. Read-only queries have no side effects. Simple calculations don’t modify state. Adding dry-run everywhere adds complexity without value.

Key Takeaways

Scattered if dry_run conditionals create code paths that drift over time. Use the gather/execute pattern instead: make dry-run produce strongly-typed instructions that execution consumes. Let the compiler enforce synchronization. Terraform’s plan/apply workflow, PowerShell’s ShouldProcess implementation, and G-Research’s functional approach all demonstrate the same principle: separate planning from execution, make the plan explicit and reviewable.

TOCTOU races are inherent to distributed systems. Dry-run shows intent, not guarantees. Add runtime validation, minimize the window between check and use, but accept that some drift is inevitable. Still, architectural discipline prevents most bugs. Compiler-enforced synchronization beats coding conventions.

If you’re building a developer tool, add dry-run support for destructive operations. Implement it right the first time: gather instructions, then execute instructions. Skip the “if dry-run / else soup.” Your users will trust your previews because your previews will match execution. That trust is worth the upfront architecture investment.

—