On January 30, 2026, The Register published a stark call to action: European firms must abandon US cloud providers. This comes just 15 days after AWS launched its EUR 7.8 billion European Sovereign Cloud, promising true digital sovereignty through technical separation. But here’s the problem: 61% of European CIOs want local cloud providers, yet 70% of Europe’s cloud market remains controlled by US hyperscalers. The central question: Can a US-owned company ever provide genuine EU sovereignty when the US CLOUD Act guarantees government access to any data controlled by American companies—regardless of where it’s stored?

The CLOUD Act vs GDPR: An Unsolvable Legal Paradox

The US CLOUD Act and EU GDPR create an unresolvable legal conflict. The CLOUD Act (2018) allows US law enforcement to compel American companies to hand over data stored anywhere in the world—Brussels, Brandenburg, or the moon. Meanwhile, GDPR Article 48 prohibits data transfer to non-adequate jurisdictions without an international agreement. No such US-EU CLOUD Act agreement exists.

The European Data Protection Board put it bluntly: providers have “very limited options to comply with CLOUD Act orders without breaching GDPR.” European strategy documents confirm “the application of the CLOUD Act is a risk to the data of EU citizens and businesses.” These laws contradict each other. If the US government issues a CLOUD Act warrant for data in AWS’s European Sovereign Cloud, AWS must choose: violate US law by refusing the warrant, or violate EU law by transferring the data. Both options create liability.

This isn’t a technical problem that better data centers can solve. It’s a legal contradiction with no resolution under current frameworks. Technical separation is irrelevant when legal jurisdiction demands access regardless of physical location.

AWS’s EUR 7.8B Bet on Technical Sovereignty

AWS launched its European Sovereign Cloud on January 15, 2026, with a EUR 7.8 billion investment betting that infrastructure separation achieves sovereignty. The architecture is genuinely isolated: an entirely separate partition (aws-eusc) with independent IAM, billing, DNS, and 90+ services. Resources in aws-eusc cannot communicate with commercial AWS. It’s operated by EU citizens—Stephane Israel and Stefan Hoechbauer—under German legal entities, with independent third-party auditing planned for 2026.

AWS’s argument: technical and operational separation creates sovereignty. However, critics argue ownership determines jurisdiction, not operations. The Gaia-X CTO stated clearly: “No US company can guarantee that the US government will never access your data.” US parent company means US CLOUD Act jurisdiction applies, regardless of where servers sit or who operates them.

Corporate law typically allows parent companies to compel subsidiaries to produce information. The CLOUD Act explicitly targets companies “under US jurisdiction.” AWS’s EUR 7.8 billion bet assumes a subsidiary structure shields data from US legal reach. Legal experts disagree. The first CLOUD Act warrant for European Sovereign Cloud data will settle this debate definitively—and AWS’s entire strategy depends on winning that test.

Developers Face an Impossible Choice

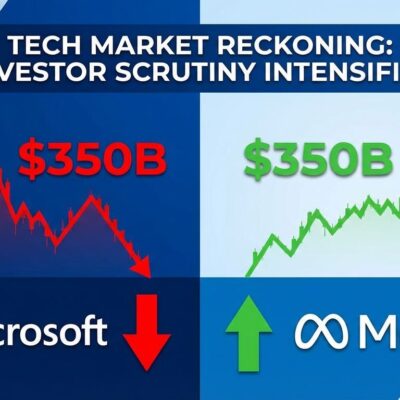

There are three options, all bad. Option A: Use US hyperscalers (AWS, Azure, Google) and accept CLOUD Act/GDPR compliance risk. Option B: Use European providers like OVHcloud or Hetzner and sacrifice features—only 4% of global cloud capacity is European-owned, with significantly limited service portfolios compared to AWS’s 200+ services. Option C: Hybrid architecture with EU clouds for sensitive data and US clouds for compute, which increases complexity and doubles operational costs.

The market reality makes escape impossible. US hyperscalers control 70% of Europe’s cloud market. European alternatives lack feature parity, mature tooling, and ecosystem depth. Migration from AWS to European providers means years of effort, millions in costs, and breaking changes to APIs your team has spent years building on. Vendor lock-in isn’t accidental—it’s the business model.

Forrester predicts no European enterprise will abandon US hyperscalers in 2026. The capability gap is too wide. European providers are improving, but they’re competing against companies with decades of infrastructure investment and engineering talent. There’s no good choice under current legal frameworks. Developers building for EU customers can’t win.

What Developers Should Do Now

The EU Cloud and AI Development Act is expected in Q1 2026, potentially mandating European clouds for sensitive data. Until then, developers must make architectural decisions with incomplete legal information.

First, assess your actual risk. If you handle EU citizen data in healthcare, finance, or government sectors, sovereignty isn’t optional—it’s regulatory. For less sensitive workloads, the GDPR risk may be acceptable. Second, don’t bet on AWS’s European Sovereign Cloud for compliance-critical workloads. The legal uncertainty makes it unsuitable until court precedent proves US government access is impossible under German law.

Third, plan for hybrid if you need both sovereignty and capabilities. Keep personally identifiable information on European providers, run compute-intensive workloads on US clouds. Yes, this is complex and expensive. That’s the cost of operating under contradictory legal regimes. Fourth, watch regulatory developments closely. The EU Cloud Act may mandate specific architectures that make your current approach non-compliant.

The bottom line: true digital sovereignty requires European ownership, not just European operations. AWS’s EUR 7.8 billion bet assumes technical separation solves legal jurisdiction. The CLOUD Act suggests otherwise. Developers can’t wait for legal clarity—architecture decisions are needed now, with or without answers.