Proton Mail users woke up this week to a marketing email about Lumo, the company’s new AI assistant. Nothing unusual—except many recipients had explicitly disabled all product update notifications. They chose Proton specifically to escape Big Tech surveillance tactics. Now Proton was using the same playbook.

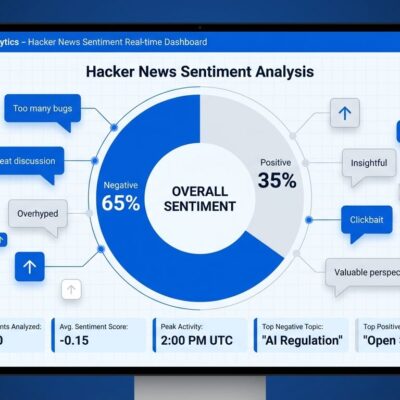

The mechanism is textbook dark pattern: create new email preference categories, default them to “enabled,” and claim previous opt-outs don’t apply to this “different” type of communication. Hacker News erupted with 384 points and 241 comments. The recurring sentiment: “If I can’t trust Proton, who can I trust?”

The answer is uncomfortable: probably no one. Because this isn’t a Proton problem—it’s proof that digital consent is fundamentally broken.

Every Company Does This

Proton is simply the latest example. The same dark pattern appears across the industry with mechanical precision:

Microsoft sends Copilot newsletters without consent, some lacking unsubscribe buttons entirely. Amazon’s pharmacy and health emails ignore opt-outs by labeling pure marketing as “transactional.” LinkedIn makes unsubscribing functionally impossible, treating communication preferences as “temporary suggestions” rather than binding choices. Apple sends promotional emails after purchases that circumvent marketing preference settings.

HN users documented the pattern: companies create granular categories, default them to opt-in, and reset preferences during “system updates.” One commenter crystallized the strategy: “If too many users unsubscribe, they just add one more category and ‘accidentally’ opt-in everyone.”

The root cause is structural. Companies control the consent interface. They write the categories, set the defaults, and define what counts as “marketing” versus “product updates” versus “essential notifications.” Asking them to respect user preferences is asking the fox to guard the henhouse.

AI Makes Everything Worse

AI isn’t creating this problem—it’s accelerating it. Proton launched Lumo in July 2025, claiming zero-access encryption and European privacy jurisdiction. Six months later, they’re using dark patterns to drive adoption.

The pressure is economic. Seventy percent of CFOs plan GenAI investments for 2025. Companies must prove users actually engage with AI features, not just that they built them. Adoption metrics drive funding rounds and valuation multiples. Aggressive marketing becomes financially necessary.

Google learned this lesson and ignored it. France’s CNIL fined Google €325 million in September 2025 for sending Gmail promotional ads without consent. Google still sends the ads. The fine was expensive theater, not a behavior change.

One HN user observed: “Seeing this far more with AI than any other advancement.” You can’t disable Gemini in Gmail without an enterprise plan. Every app now injects AI into every interaction, consent be damned. The AI hype cycle creates urgency that overrides whatever ethical guardrails companies claim to maintain.

Why Penalties Don’t Work

Regulation exists. GDPR allows fines up to €20 million or 4% of global revenue. CAN-SPAM Act permits penalties of $51,744 per violating email. On paper, these should deter abuse.

In practice, they’re rounding errors. HelloFresh’s UK spam campaign generated fines of £0.002 per message—trivially profitable to ignore. Microsoft faces GDPR complaints but continues sending Copilot newsletters. The cost-benefit is clear: the value of engagement metrics exceeds the risk-adjusted penalty.

Companies treat fines as a cost of doing business. Penalties arrive years after violations. Meanwhile, AI adoption metrics justify continued investment today. By the time regulators act, the damage is done and the financial benefit is already captured.

Privacy Companies Aren’t Immune

Proton’s violation stings particularly because the company positioned itself as an ethical alternative. The Lumo announcement emphasized privacy: “not used for training,” “zero-access encryption,” “European jurisdiction.” These claims differentiated Proton from Big Tech competitors.

Yet when facing the same economic pressures, Proton chose the same tactics. Users who set up Proton as honeypot addresses—email accounts used solely to track where contacts leak—reported the only spam they received came from Proton itself. Paying customers migrated to Fastmail and Tuta, citing both spam and usability issues.

One HN commenter captured the dynamic: “Your reputation is your moat. If you ruin it by acting like Google, you’re filling your own moat.” Proton’s competitive advantage was trust. That trust is now compromised.

The deeper lesson: this proves the problem is economic, not cultural. Even companies with stated privacy-first values succumb when growth metrics demand it. No provider is immune.

What Actually Needs to Change

Individual action helps at the margins. HN users recommend marking unwanted emails as spam rather than unsubscribing—it trains filters and harms sender reputation. Using email aliases per service tracks which companies sell your data. Self-hosting provides complete control.

But these are band-aids. The structural problem requires structural solutions.

First, consent management must move to third parties. Companies cannot simultaneously need your engagement and control your opt-out interface. The conflict of interest is irreconcilable.

Second, defaults must flip. Current systems assume consent unless you explicitly opt out. The correct model: silence is disagreement. Companies should require explicit opt-in for each communication category, not create new categories to bypass previous choices.

Third, penalties must exceed the value extracted. Dark patterns persist because they’re profitable. Fines need to hurt—percentage of revenue calculations that actually impact decision-making, plus criminal liability for executives who approve these tactics.

Current regulations are performative. GDPR sounds strict until you realize Google paid €325 million and changed nothing. CAN-SPAM exists but enforcement is nearly non-existent. The illusion of accountability without the substance.

Proton’s AI marketing debacle isn’t unique. It’s a symptom of a system where consent is theater, regulation is toothless, and economic incentives override every stated principle. Until that changes, your inbox will continue to fill with emails you explicitly opted out of receiving. And “privacy-focused” won’t mean what you think it means.