On December 22, 2025, Google’s parent company Alphabet announced a $4.75 billion acquisition of Intersect Power, a renewable energy and data center developer. The deal isn’t about expanding Google’s software capabilities or acquiring AI talent. It’s about securing something far more fundamental: electricity. As Intersect CEO Sheldon Kimber put it, “AI today is stuck behind one of the slowest, oldest industries in the country: electric power. The country has racks full of GPUs that can’t be energized because there isn’t enough electricity.” For the first time in the AI era, the limiting factor isn’t algorithms or training data. It’s kilowatts.

Google Buys Its Way Out of an Energy Crisis

The Intersect acquisition marks the first time a Big Tech company has purchased a major renewable energy developer outright. For $4.75 billion in cash plus assumed debt, Google gains access to a 10.8-gigawatt power pipeline expected by 2028, with 7.5 GW already operational and another 8 GW in development. The deal is expected to close in the first half of 2026.

Intersect’s business model is built on co-locating data centers with dedicated gas and renewable power generation, effectively bypassing the grid bottlenecks that have plagued AI infrastructure expansion. This isn’t a partnership or a power purchase agreement—it’s vertical integration. Google is taking control of the power generation timeline itself, rather than waiting on utilities that can’t keep up with AI’s exponential energy demands. The acquisition announcement signals a strategic shift across the entire tech industry.

The AI Industry’s Dirty Secret: Not Enough Power

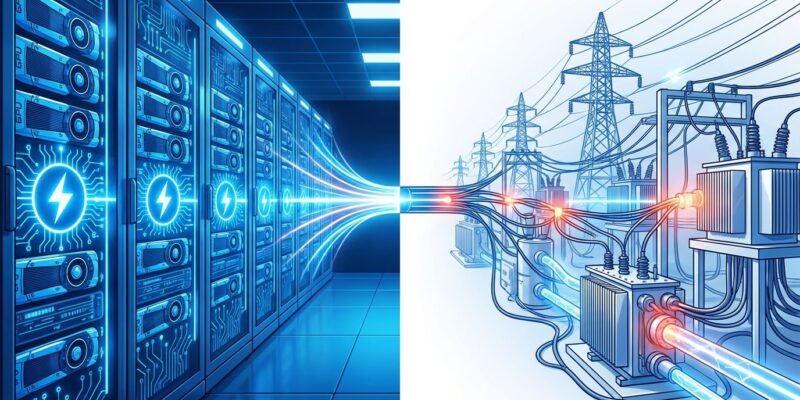

Here’s what most developers don’t realize: AI servers consume roughly 10 times more power than standard servers. A typical CPU or storage server draws about 1 kilowatt. An AI server? Over 10 kW, driven by GPU-intensive workloads. Training workloads can demand 100 to 200+ kilowatts per rack, with some frontier systems hitting 1 megawatt per rack.

The problem gets worse when you consider that 80-90% of AI computing power now goes toward inference, not training. Training is a burst event—expensive, but time-limited. Inference is continuous. Every ChatGPT query, every AI-generated image, every real-time recommendation system is pulling power 24/7. That sustained load is what’s breaking the grid.

Data center electricity consumption hit 415 terawatt-hours in 2024, representing about 1.5% of global electricity use. By 2030, that’s projected to double to 945 TWh. In the U.S. alone, AI is pushing toward 100 gigawatts of new demand by 2030. And here’s the kicker: power constraints are extending data center construction timelines by 24 to 72 months. The infrastructure bottleneck is real, and it’s not getting better anytime soon.

This is, as one industry analysis put it, “the definitive end to the era where AI was seen purely as a software challenge.” It’s now a race for land, water, and most critically, electricity.

Everyone’s Spending Hundreds of Billions

Google isn’t alone in this scramble. Meta is planning to spend $66 to $72 billion on AI infrastructure in 2025, with CEO Mark Zuckerberg committing “hundreds of billions of dollars” for the company’s superintelligence pursuit. Meta is building its first gigawatt-scale supercluster, codenamed “Prometheus,” set to come online in 2026, with plans for “Hyperion” to scale up to 5 GW. Microsoft, meanwhile, is spending $140 billion on capital expenditures in 2025 alone—triple its fiscal 2024 figure and up 58% year-over-year.

Collectively, Alphabet, Meta, Microsoft, and Amazon are pouring over $380 billion into AI infrastructure this year. To put that in perspective, training GPT-4 cost over $100 million and consumed 50 gigawatt-hours of electricity—equivalent to San Francisco’s three-day power usage. And that was just training one model, once. The compute arms race is driving unprecedented capital deployment, and every dollar is chasing the same scarce resource: reliable, scalable power.

What This Means for Your Cloud Bill

For developers, the implications are direct and unavoidable. Wholesale electricity costs have jumped 267% over the past five years in regions near major data centers, and those costs are being passed on to cloud customers. Residential electricity bills in some markets are rising $16 to $18 per month due to AI data center demand, with projections showing an 8% average increase in U.S. bills by 2030—potentially hitting 25% in high-demand markets like Virginia.

Cloud AI pricing will continue climbing as energy scarcity tightens. Deployment delays due to capacity constraints are becoming routine. This is why edge computing is gaining momentum. Gartner projects that by 2028, 75% of enterprise-generated data will be processed at the edge rather than in centralized cloud data centers. The shift makes economic sense: distributing inference workloads across edge devices reduces the strain on power-constrained cloud infrastructure.

The emerging architectural pattern is hybrid: use the cloud for training and bulk computation where massive GPU clusters are justified, but run inference at the edge where latency and cost matter. Infrastructure decisions are no longer just technical trade-offs—they’re strategic business choices shaped by energy availability.

The AI Arms Race Is an Energy Arms Race

Google’s $4.75 billion acquisition of Intersect is more than a business deal. It’s an admission. Big Tech waited too long to address the infrastructure constraints that were always going to limit AI scaling, and now they’re scrambling to buy their way out of a crisis they created. Software problems can be solved with code and clever engineering. Power plants take years to build, require massive capital, and depend on physical infrastructure that doesn’t move at software speed.

Developers are paying the price through higher cloud costs, capacity limits, and deployment delays. The lesson is clear: if you’re building AI-dependent systems today, you need to factor infrastructure constraints into your architecture now. The era of assuming infinite, affordable cloud compute is over. The new reality is finite, expensive, and constrained by the oldest limitation of all—the availability of electricity.