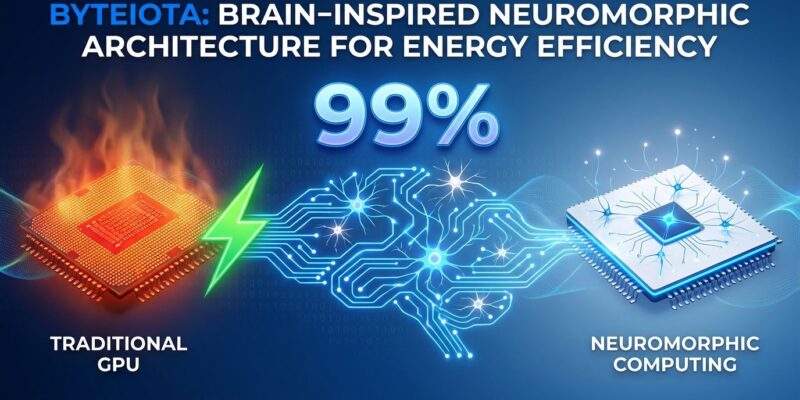

While the AI industry debates its carbon footprint, University of Surrey researchers just dropped a 99% energy reduction using brain-inspired neuromorphic computing. The breakthrough comes as US data centers gulp down 183 terawatt-hours annually and face a projected doubling to 426 TWh by 2030. The solution? Stop connecting every neuron to every other neuron like we’re still running mainframes in the ’70s.

The Brain-Inspired Breakthrough

The Topographical Sparse Mapping (TSM) algorithm, published this month in Neurocomputing, mimics how the human brain’s visual system actually works. Traditional deep learning connects every neuron in one layer to all neurons in the next, burning energy like it’s free. TSM connects each neuron only to nearby or related ones, cutting the fat without sacrificing accuracy.

Lead researcher Mohsen Kamelian Rad’s enhanced version (ETSM) adds biologically inspired pruning during training, similar to how brains refine neural connections as they learn. The result: 99% sparsity while matching or exceeding traditional AI accuracy on benchmarks, using less than 1% of the energy. That’s not incremental improvement. That’s a paradigm shift.

From Lab to Production

Neuromorphic computing isn’t theoretical anymore. Sandia National Laboratories now operates two of the world’s largest neuromorphic systems, and the specs matter.

Intel’s Hala Point packs 1.15 billion neurons and 128 billion synapses into a microwave-sized chassis, consuming a maximum 2,600 watts. Compare that to SpiNNaker’s comparable 100kW system—Hala Point runs at 3% of the power while delivering 10x the neuron capacity and 12x the performance. The system achieves 15 TOPS/W efficiency without requiring batch processing, meaning real-time inference at a fraction of traditional GPU costs.

NERL Braunfels, built on SpiNNaker2 chips and deployed in March 2025, houses 175 million neurons—roughly a small mammal’s brain power. It’s 18 times more efficient than GPUs and focused on national security applications. When government labs invest in production deployments, not just research prototypes, the technology has crossed the credibility threshold.

Market Explosion Signals Shift

The neuromorphic computing market is projected to explode from $2.60 billion today to $61.48 billion by 2035, a 33.32% compound annual growth rate. Industry insiders call 2025 the “breakthrough year” for neuromorphic’s transition from academic curiosity to commercial product.

BrainChip secured $25 million for edge AI processors. Intel scaled past 1 billion neurons. Innatera launched the first mass-market neuromorphic microcontroller. Mercedes-Benz spun off Athos Silicon specifically to develop next-generation automotive chips. These aren’t pilot programs—they’re bets on a post-GPU future.

The timing makes sense. By 2030, AI will account for 35-50% of data center power consumption, adding 220 million tons of carbon emissions globally. That’s equivalent to adding 5 to 10 million cars to US roads. Sustainability isn’t a nice-to-have anymore; it’s a business imperative with a price tag.

Autonomous Vehicles Get 90% More Efficient

Mercedes-Benz isn’t investing in neuromorphic for the press releases. The company projects 90% reduction in energy consumption for autonomous driving data processing compared to current systems. Neuromorphic processors enable 10x more efficient perception, better recognition of traffic signs and lanes in poor visibility, and ultra-low latency for safety-critical computations.

The efficiency gains directly extend EV range—a real problem when your self-driving system is draining the battery. But there’s a catch: ISO 26262 certification for safety-critical automotive systems remains years away. Great tech, real benefits, but not ready for your production vehicle tomorrow.

The Developer Ecosystem Problem

Hardware breakthroughs mean nothing without software to run on them. Neuromorphic’s Achilles’ heel is the fragmented, immature developer ecosystem. Intel’s Lava framework provides abstractions for Loihi chips. Norse offers PyTorch-based tools for spiking neural networks. The Neuromorphic Intermediate Representation (NIR) promises cross-platform compatibility. But code written for one neuromorphic platform rarely transfers to another, and that fragmentation kills adoption.

The barrier to entry remains high—developers need Python, C++, framework-specific knowledge, and often embedded systems expertise for edge deployments. Until neuromorphic computing gets its equivalent of CUDA or PyTorch (standardized, well-documented, broadly adopted), the technology stays niche despite superior efficiency.

The industry recognizes this. Software tools are maturing, and high-level programming languages designed specifically for neuromorphic architectures are in development. But we’re talking years, not months, before the average developer can pick up neuromorphic as easily as spinning up a GPU instance.

The Energy Problem Meets Its Solution

AI’s energy crisis has a solution, validated by production deployments and backed by billions in market projections. The 99% energy reduction isn’t marketing—it’s peer-reviewed research deployed at national laboratories. But technology alone doesn’t drive adoption. Neuromorphic computing needs standardized frameworks, mature tooling, and a developer community that doesn’t require a PhD to get started.

The hardware is ready. The applications are real. The market is massive. Now the software ecosystem needs to catch up before AI’s energy consumption becomes environmentally untenable.