Kroger just admitted its $2.6 billion automation bet failed spectacularly. The grocery giant is closing three robotic fulfillment centers, paying Ocado $350 million to exit their partnership, and pivoting back to traditional stores. The culprit? Kroger optimized for cost efficiency while American customers demanded delivery speed. It’s the classic tech trap: building the wrong solution to the right problem. Just because you can automate doesn’t mean you should.

The Seven-Year, $2.6B Miscalculation

In May 2018, Kroger and UK robotics firm Ocado announced an exclusive U.S. partnership to build 20 highly automated customer fulfillment centers. The pandemic online grocery surge validated their vision. By 2022, eight CFCs were operational across Monroe (Ohio), Dallas, Atlanta, Denver, and Detroit, processing orders with swarm robots on 3D grids at 99.99% accuracy.

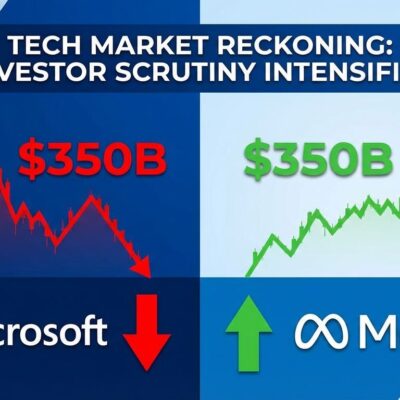

Then reality hit. In December 2025, Kroger announced it was closing three facilities in San Antonio, Birmingham, and Oklahoma City, taking a $2.6 billion impairment charge and paying Ocado $350 million in cash to compensate for the closures. The Charlotte, North Carolina CFC planned for 2026? Canceled. Only five CFCs remain operational.

The numbers tell the story. Kroger bet on 15-20% online grocery penetration by 2025. Reality delivered 13.8%. The CFCs operated “far below the utilization levels needed to justify their cost structure,” particularly facilities located outside major cities with insufficient order volumes and long delivery distances.

Speed Beats Efficiency Every Time

Kroger built for tomorrow’s rational consumer. Americans wanted today’s instant gratification.

The automation strategy assumed customers would trade delivery speed for lower prices. Next-day scheduled delivery from robotic warehouses would undercut competitors through operational efficiency. It was a perfectly logical plan that completely ignored American consumer behavior.

While Kroger optimized cost-per-order, Instacart and DoorDash won the market with 30-minute delivery. DoorDash captured 33% of U.S. grocery delivery platform sales in 2025, with Instacart and Uber Eats each claiming roughly 20%. All three grew double digits year-over-year using the same asset-light model: existing stores plus gig workers.

Kroger optimized for the wrong metric. No amount of robotics can fix solving the wrong problem.

Asset-Light Beats Capital-Intensive

Here’s the irony that should make every CFO wince: Kroger’s 2,700 grocery stores were the answer all along.

While Kroger locked billions into specialized robotic infrastructure, competitors stayed flexible. When 30-minute delivery became the standard, Instacart and DoorDash scaled effortlessly. Kroger couldn’t pivot—the capital was sunk, the facilities were built, and the robots only knew how to optimize for efficiency, not speed.

In uncertain markets, flexibility beats efficiency. The $2.6 billion impairment charge is the cost of strategic inflexibility. Kroger now acknowledges that its stores “give us a way to reach new customer segments and expand rapid delivery capabilities without significant capital investments.” That realization came seven years and billions of dollars too late.

The Automation Hype Trap

Kroger didn’t ignore the warning signs—they dismissed them.

In mid-2023, CEO Rodney McMullen told investors Kroger would “hold off on building new e-commerce sites until we make sure that we have a clear path on the ones we have.” That same year, the company quietly closed three spoke facilities in Texas and Florida. By September 2025, Kroger announced a review of automated warehouses, shifting focus to store-based delivery.

The automation narrative was too compelling to question. Ocado’s technology worked brilliantly in the UK, cutting costs 50% since 2020 through high-density urban fulfillment. The tech promised to revolutionize grocery delivery. Venture capital loved the story. Leadership committed.

What works at Amazon scale—high predictable volume, controlled environments, decades to amortize costs—doesn’t transfer to uncertain grocery markets with razor-thin margins and rapidly shifting consumer expectations. Automation works when utilization is high and demand is stable. Kroger had neither.

The Framework Kroger Ignored

Here’s the decision framework that could have saved Kroger billions:

Don’t automate when:

• Demand is uncertain (market penetration stalled at 10-13%, not the projected 15-20%)

• Customer preferences are rapidly changing (cost-conscious to speed-obsessed)

• You’re in a low-margin business with high capital requirements

• Asset-light alternatives exist (2,700 stores, gig workers)

• Early data contradicts your projections (2023 closures, CEO warnings)

Automate when:

• Volume is high and predictable (Amazon fulfillment centers)

• Requirements are stable over decades

• Margins support capital intensity

• The efficiency gain directly solves what customers value

Kroger failed every red flag test and proceeded anyway. The automation-first mindset overrode market signals.

The Real Lesson

This isn’t just a retail cautionary tale. Every tech leader making build-versus-buy or automate-versus-manual decisions faces the same trap.

Kroger optimized operations before understanding customers. They built for efficiency when the market valued speed. They locked capital into inflexible infrastructure when competitors stayed light and adaptable. They assumed technology would create demand rather than testing whether demand existed.

The $2.6 billion writeoff teaches what every failed automation project eventually reveals: customer behavior beats operational efficiency. Test assumptions before massive investments. Know when not to automate. And sometimes—often—the low-tech solution wins.

Kroger spent seven years and billions of dollars learning what their stores could have told them on day one: Americans don’t optimize grocery shopping. They want food delivered fast. The robots never had a chance.