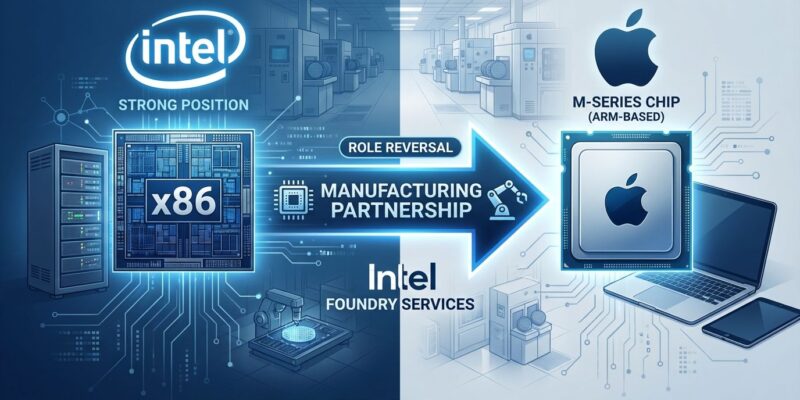

Intel is in talks to manufacture Apple’s entry-level M-series chips by 2027 using its 18A process node, according to reports this week from supply chain analyst Ming-Chi Kuo. Five years after Apple abandoned Intel’s x86 processors for ARM-based chips citing “manufacturing delays” and performance failures, Intel will now produce the very processors that made Intel obsolete in Macs. It’s the ultimate tech industry role reversal: partner to competitor to contractor.

The irony is almost too perfect. Intel couldn’t deliver competitive chips, so Apple designed its own. Now Intel gets to make them—not because it won the technology war, but because Apple needs a backup plan for its Taiwan problem.

The Geopolitical Angle Everyone’s Missing

This isn’t about technology. It’s about supply chain chess. TSMC manufactures roughly 90% of the world’s advanced chips, all concentrated in Taiwan. With US-China tensions escalating over Taiwan, Apple faces an existential supply chain risk. One geopolitical crisis could cripple Mac and iPad production overnight.

Intel’s North American 18A fabs solve this problem. According to Kuo, the deal appeals to “Made in USA” preferences while diversifying away from Taiwan dependency. Apple isn’t replacing TSMC—it’s adding insurance. Entry-level M-series chips (likely M6 or M7) for MacBook Air and iPad will come from Intel, targeting 15-20 million units annually starting in 2027. High-end chips for MacBook Pro and Mac Studio stay with TSMC.

Smart hedging. If Intel’s 18A fails, Apple’s flagship products remain unaffected. If Taiwan becomes inaccessible, Apple can still ship entry-level Macs.

Intel’s Make-or-Break Foundry Bet

For Intel, landing Apple validates everything. Former CEO Pat Gelsinger’s “5N4Y” strategy—five production nodes in four years—bet billions on Intel becoming a competitive contract manufacturer after years of humiliating manufacturing failures. The Apple deal proves Intel 18A works. Or it’s a desperate grab for relevance from a company that’s lost its edge.

Intel 18A is legitimately impressive on paper. It’s the first sub-2nm node manufactured in North America, featuring RibbonFET gate-all-around transistors and PowerVia backside power delivery. Intel claims 25% better performance or 36% lower power consumption compared to its previous generation. The company even beat TSMC’s competing N2 node to production by weeks.

However, Intel has overpromised on process nodes before. The question isn’t whether 18A looks good in benchmarks—it’s whether Intel can deliver at Apple’s scale without yield disasters or delays. Apple is beta-testing Intel’s manufacturing comeback with low-stakes chips. If Intel fails here, the entire foundry strategy collapses. If it succeeds, Intel proves it can compete with TSMC as a contractor, even if it lost the processor war.

Timeline and What Could Go Wrong

Apple has already received Intel’s 18AP process design kit and is running simulations. Volume production starts late 2026, with chips shipping in MacBook Air and iPad products by mid-2027. That’s aggressive for unproven technology at Apple’s volume requirements.

Intel’s history doesn’t inspire confidence. This is the company that delayed 10nm for years, ceded manufacturing leadership to TSMC, and forced Apple to design its own chips. Gelsinger left Intel in December 2024 after his turnaround efforts failed to deliver financial results. Consequently, new CEO Lip-Bu Tan inherits this pressure-cooker timeline with everything riding on 18A execution.

If Intel misses the 2027 target, it reinforces exactly why Apple left in the first place. If yields come in below expectations, Apple has TSMC as backup—but Intel’s reputation as a contract manufacturer is finished before it starts.

Why This Matters Beyond Apple

This deal is bigger than two companies. It’s a test case for US semiconductor independence. If Intel can manufacture Apple’s chips competitively, other companies will follow. Moreover, Intel’s target of $15 billion in annual external foundry revenue by 2030 depends on proving 18A at scale with a demanding customer.

Conversely, if Intel stumbles, it confirms TSMC’s monopoly on advanced manufacturing is unbreakable. Taiwan remains the critical chokepoint for global tech, and geopolitical risks remain unmitigated.

Apple is placing a calculated bet: entry-level chips only, with TSMC handling anything that matters. Intel gets one chance to prove it’s solved the manufacturing problems that cost it Apple’s business in the first place. Whether this is redemption or desperation depends entirely on what ships in 2027.