On November 29, 2025, software engineer Sean Goedecke dropped an uncomfortable truth on Hacker News that sparked 173 comments and three warring camps: the code you’re ashamed of probably isn’t your fault. His article, “How good engineers write bad code at big companies,” argues bad code at major tech companies isn’t individual failure—it’s an organizational choice. Companies deliberately treat engineers as fungible resources (average 1-2 year tenure) while codebases live for decades, creating a perpetual stream of “beginners” making changes to unfamiliar systems under deadline pressure.

Companies Think They’re Going Fast. The Data Says Otherwise.

Here’s the paradox: companies believe they’re trading quality for speed. However, research proves the opposite.

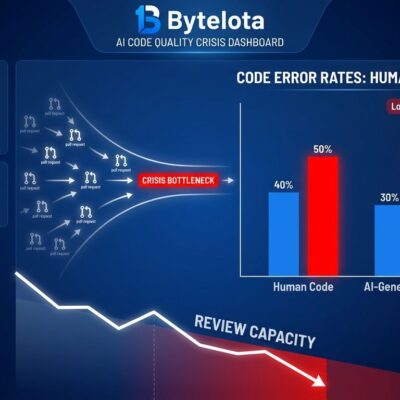

CodeScene’s Code Red Study analyzed 39 commercial codebases and found high-quality code delivers 15 times fewer bugs and twice the development speed. Tasks in unhealthy code take up to 10 times longer. Moving from code health score 6.0 to 8.0 allows teams to iterate 33% faster. Yet technical debt consumes 40% of IT budgets—$2.41 trillion annually in the US. Moreover, developers spend 42% of their time (13.5 hours weekly) dealing with debt and bad code.

The velocity paradox bites harder than management admits. Companies optimize for “flexibility”—the ability to redeploy talent rapidly—but pay for it with hidden velocity costs. Furthermore, as HN commenter asdfman123 noted, “Management doesn’t care about good code, it cares about results.” Those who ship sloppy code get promoted. The system rewards speed theater while accumulating debt that eventually paralyzes the organization.

You’re Judged on Quality You Can’t Control

This is where Goedecke’s thesis hits home: engineers are structurally set up to fail.

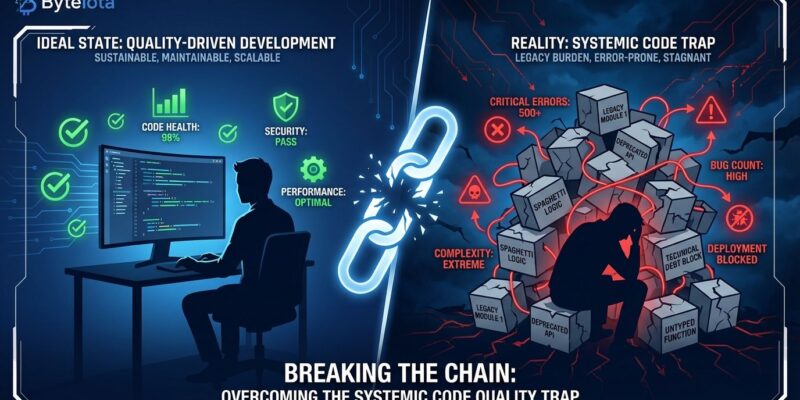

You’re forced to work on unfamiliar codebases under deadline pressure, producing what Goedecke calls “impure engineering”—then blamed when quality suffers. Management uses inherited technical debt to deny promotions. Consequently, HN commenter jagged-chisel captured it perfectly: engineers are “held accountable for bad results” caused by code written by departed engineers. Additionally, another commenter (mikert89) noted architectural mistakes that cause multi-year debt never surface in code reviews—reviews catch syntax, not design flaws.

Meanwhile, the architects who built bad systems become indispensable. Perverse incentive.

You’re hired for expertise, then deliberately prevented from developing it. Average tenure at FAANG historically clocked in at 1-2 years (Google 1.9, Amazon 1.84, Meta 2.02). Internal mobility means engineers rarely stick with a single codebase longer than 3 years. However, codebases persist for decades. This creates a permanent majority of “beginners”—engineers onboarded within 6 months to the company, codebase, or language. As HN commenter zmj summarized: the core thesis is “do what the company wants, even if it’s not right.” In fact, that’s not engineering. That’s manufacturing consent.

The Debate: Inevitable, Fixable, or Exaggerated?

The 173-comment HN thread fractured into three distinct camps, exposing fundamental disagreement about solutions.

Camp 1 (Systemic/Economic) sees this as worker alienation. HN commenter Herring simply linked to Marx’s alienation theory, suggesting nothing new here—capitalism treating engineers as fungible resources. Moreover, commenter kcexn explained the business logic: “Large projects that don’t depend on irreplaceable individuals are more repeatable.” Companies gain flexibility, engineers lose craft. The system wins.

Camp 2 (Craft/Pride) refuses resignation. HN commenter ajkjk: “It’s just depressing…it sucks to be doing bad work.” These engineers emphasize intrinsic motivation—craftspeople naturally desire quality work. They advocate fighting for excellence despite organizational pressure: “better than I found it” principle, refuse to merge bad patches. Nevertheless, even they acknowledge individual powerlessness against structural forces.

Camp 3 (FAANG Exceptionalism) argues top companies escape this pattern. One commenter with 25+ years observation claimed “code quality is shockingly good” across FAANG. Talent correlates with compensation. Better practices exist. The pushback? Even Google has high turnover. Therefore, “good for big tech” still worse than healthy long-term ownership.

The split reveals the deeper question: Is this capitalism doing capitalism things (inevitable) or culture failure (fixable)? Most telling: even those who think it’s fixable admit individual engineers are powerless.

This Model Only Works With Infinite Hiring

Goedecke’s implicit warning: this trajectory is unsustainable.

Companies burn through engineers every 1-2 years, relying on fresh talent to replace departed expertise. The model only works with an infinite hiring pipeline. However, 2025 signals a shift—tenure is rising at “unprecedented pace” since 2023, according to Pragmatic Engineer data. Consequently, if turnover slows due to market conditions (layoffs, economic slowdown, demographic limits), the technical debt chickens come home to roost.

HN commenter mikert89 warned: “1 year of quick development could stun org for next five years.” When you can’t hire fast enough to outrun accumulated debt, velocity collapses. Moreover, commenter nosianu described the inheritance problem: “Picking up one spaghetti string…always ending up with the whole bowl.”

If historical tenure (1.9 years) doubles to 4 years, do companies adapt or collapse under debt weight? The 2025 tenure rise might signal the end of this era—or just a temporary blip before the next boom. Either way, the structural problem remains unaddressed. Companies are leveraged on perpetual churn.

Are You in the Trap Right Now?

Goedecke’s article forces uncomfortable self-reflection. Answer honestly:

Are you writing bad code today? How many bugs this week were from departed engineers? Does your company’s “flexible” org structure actually feel rigid? Count the bugs. Calculate time spent on inherited debt versus new features. The numbers don’t lie.

HN commenter pxc: “Excellent code…is probably more often ‘gotten away with’ than commissioned.” Another (lukan) quoted Douglas Adams on deadline absurdism—arbitrary timelines treated as immutable laws. These aren’t rhetorical questions. They’re diagnostic.

Most engineers already know the answers. Furthermore, they’re just waiting for permission to say it out loud: “This isn’t my fault. The system is broken.” Goedecke gave them that permission.