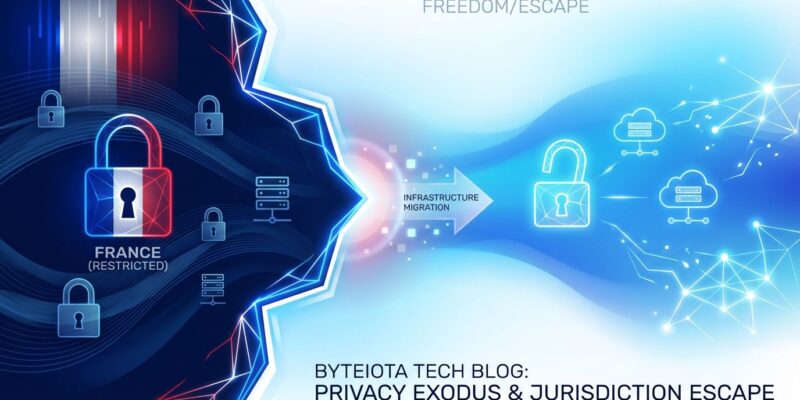

GrapheneOS, a privacy-focused Android operating system, announced this week it’s evacuating all server infrastructure from France after a November 19 Le Parisien report labeled it a “secret weapon for drug traffickers.” The privacy project is moving servers from French provider OVH to Canada, Germany, and the US, interpreting the coverage as an implicit government threat: provide backdoors or face legal consequences. This marks the first time a major Western privacy project has completely exited a democratic country’s jurisdiction over encryption policy—demonstrating that infrastructure migration, not legal battles, can be the winning strategy against authoritarian pressure.

French Police Label Privacy Tool as “Criminal Weapon”

French judicial police (OFAC) told Le Parisien on November 19 that GrapheneOS enables drug traffickers to hide communications, citing security features like Auto-Reboot and Duress PIN that frustrate investigations. Auto-Reboot automatically returns phones to their most secure encrypted state after periods of inactivity, while Duress PIN irreversibly wipes data under coercion—both legitimate privacy protections that happen to make law enforcement’s job harder.

The GrapheneOS team interpreted the coverage as a direct threat. “We don’t have user data to hand over,” they stated. “What they mean by ‘cooperate’ is backdoors.” France didn’t need formal legal action—simply having law enforcement label a privacy tool as criminal in major media creates reputational damage and implied consequences. The team also accused French competitors Murena and iodé of orchestrating the smear to eliminate competition in the European de-Googled Android market.

Complete Infrastructure Exodus Within 48 Hours

Within two days of the Le Parisien article, GrapheneOS announced a complete withdrawal from France. All servers hosted by OVH—a major French cloud provider—are migrating to Toronto (Mastodon, Discourse, Matrix), Germany via Netcup (critical website infrastructure), and US providers. The project also banned team members from traveling to or working from France, declaring the country “no longer safe for open source privacy projects.”

This isn’t policy protest—it’s actual geographic exile. GrapheneOS demonstrates what Apple and Google cannot: the ability to escape government pressure by relocating infrastructure beyond a jurisdiction’s reach. France gains nothing from this exchange. No backdoor, lost business from OVH, and a clear signal to the tech industry that France is hostile territory for privacy technology. GrapheneOS continues operating normally, just from elsewhere.

Related: Browser Fingerprinting: Privacy Nightmare You Can’t Clear

France’s Pattern of Failed Encryption Backdoor Attempts

The GrapheneOS incident fits a broader pattern of French government pressure on encryption. In March 2025, France’s “Narcotrafic” bill would have forced encrypted messaging services to provide decrypted data within 72 hours. Civil society groups and privacy advocates pushed back hard enough that the National Assembly rejected the measure. France also supports the EU Chat Control proposal, which would mandate scanning all private messages—effectively creating encryption backdoors for everyone.

However, Germany blocked Chat Control in October 2025, creating a “blocking minority” that makes passage mathematically impossible. German Justice Minister Stefanie Hubig was direct: “Random chat monitoring must be taboo in a constitutional state. Germany will not agree to such proposals at the EU level.” The internal EU division shows France’s encryption hostility isn’t universal, but the pattern demonstrates persistent government pressure throughout 2025.

Security Experts: Backdoors Break Security for Everyone

GrapheneOS can’t simply “cooperate” because encryption backdoors fundamentally break security for everyone. Apple established this principle in 2016 when the FBI demanded an iPhone backdoor for the San Bernardino case. Apple CEO Tim Cook’s response remains definitive: “If the FBI had a tool to extract information for legitimate reasons, criminals could use that same tool to extract health or financial data, and foreign governments could use it to spy on Americans.”

Historical evidence supports this position. The NSA’s EternalBlue exploit—a government-developed backdoor—was leaked in 2017 and weaponized by WannaCry and NotPetya ransomware, causing billions in damages worldwide. Security practitioners are clear: once a vulnerability exists, it doesn’t stay in the hands of the “good guys” for long. The FBI even overstated the “going dark” problem, claiming investigators were locked out of 7,800 devices when the actual number was closer to 1,000-2,000.

The Bigger Question: Where Can Privacy Tech Operate?

GrapheneOS’s exodus raises critical jurisdictional questions for every privacy project. France demonstrated hostility with two backdoor attempts in 2025. The UK pressured Apple into withdrawing Advanced Data Protection in February 2025 under the Investigatory Powers Act. Parts of the EU support Chat Control. These aren’t isolated incidents—they’re a pattern of Western democracies demanding encryption access.

Germany just blocked Chat Control and declared surveillance unconstitutional. Switzerland maintains strong privacy traditions. The US has First Amendment protections for privacy technology despite ongoing political pressure. Privacy projects now face strategic calculations about where to maintain infrastructure, similar to how companies forum-shop for favorable tax jurisdictions. The difference is that infrastructure migration works as a counter-strategy—GrapheneOS proved it this week.

Key Takeaways

- GrapheneOS completely exited France after implicit government threats following a November 19 report labeling it a “criminal tool,” demonstrating that infrastructure migration is an effective response to authoritarian pressure on encryption.

- France attempted encryption backdoors twice in 2025—the rejected Narcotrafic bill and ongoing Chat Control support—showing persistent government hostility toward privacy technology despite civil society opposition.

- Security experts and major tech companies consistently warn that encryption backdoors create systemic vulnerabilities. Apple’s 2016 fight with the FBI established that “backdoors for good guys” inevitably become tools for criminals and hostile governments.

- Privacy projects now face jurisdictional calculations about where to safely operate. France and the UK have demonstrated hostility, Germany blocked Chat Control, while the US maintains First Amendment protections despite political pressure.

- France gained nothing from pressuring GrapheneOS—no backdoor, lost business from OVH, damaged reputation—while GrapheneOS continues operating from Canada, Germany, and the US. The outcome demonstrates limits of governmental pressure when targets can relocate.

The GrapheneOS case sets a precedent: privacy technology can escape national jurisdiction through infrastructure migration. Whether this approach scales as more governments demand access remains unclear, but for now, geographic exit beats legal compromise.