David Heinemeier Hansson, creator of Ruby on Rails, removed TypeScript from the Turbo framework in 2024. His reasoning? TypeScript’s complexity doesn’t justify its benefits. This sparked one of tech’s most divisive debates: Is TypeScript over-engineering JavaScript?

Every JavaScript developer faces this decision. The community splits sharply. Pro-TypeScript developers call it essential. Critics argue it’s cargo cult complexity. The answer depends on project scale, team size, and whether you value compile-time safety over velocity.

Here’s the contrarian take: TypeScript solves real problems but creates bigger ones. For 80% of projects, the complexity cost outweighs the bug-prevention benefit.

The TypeScript Tax Nobody Discusses

TypeScript tutorials sell the benefits. Type safety prevents bugs. IDE autocomplete improves. Refactoring gains confidence. These benefits are real. What’s rarely mentioned are the costs.

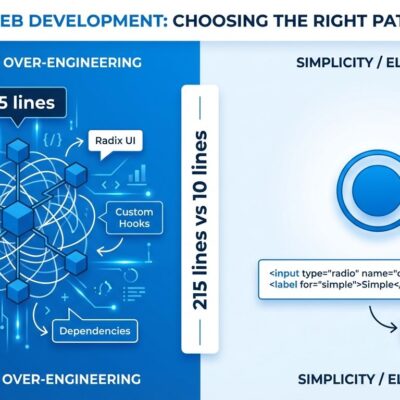

Build complexity is the first tax. TypeScript requires transpilation. Your simple JavaScript project now needs TypeScript compiler, Babel, or esbuild. Configuration files multiply. A vanilla JavaScript project uses 3-5 dev dependencies. TypeScript projects average 8-12. You’re maintaining tooling instead of building features.

Configuration overhead is the second tax. A minimal tsconfig.json requires 40-60 options. Developers spend hours debugging configuration instead of writing code. This complexity rivals webpack at its worst.

Type definitions are the third tax. Thirty percent of npm packages lack proper TypeScript definitions. The @types/* packages on DefinitelyTyped lag behind actual libraries. Sometimes they’re just wrong. You’re debugging two codebases: the library and its type definitions.

The velocity tax is the hidden cost. Compare writing a simple function:

// JavaScript: 30 seconds

function getUserData(id) {

return fetch(`/api/users/${id}`).then(r => r.json());

}

// TypeScript: 5 minutes

interface User {

id: number;

name: string;

email: string;

createdAt: Date;

preferences: UserPreferences;

}

interface UserPreferences {

theme: 'light' | 'dark';

notifications: boolean;

}

async function getUserData(id: number): Promise<User> {

const response = await fetch(`/api/users/${id}`);

return response.json();

}Prototyping slows to a crawl. Rapid iteration dies under type definitions. This matters for MVPs and early-stage products where speed beats safety.

DHH isn’t alone. The Svelte team removed TypeScript from core development to increase velocity. They kept TypeScript support for users but recognized the internal cost. Small teams frequently try TypeScript for six months, then revert to JavaScript after fighting types more than fixing bugs.

Type Safety is Type Theater

TypeScript’s core value proposition is catching bugs at compile time. This sounds compelling until you examine what types actually prevent.

Logic bugs still happen. Types can’t catch “should this variable be multiplied by 100 or divided by 100?” Business logic errors and algorithm mistakes pass type checking. Your tests matter more than your types for catching real bugs.

Runtime errors happen regardless. External data from APIs, user input, environment variables—none comes with TypeScript guarantees. Consider this “type-safe” code:

interface User {

id: number;

name: string;

}

async function getUser(id: number): Promise<User> {

return fetch(`/api/users/${id}`).then(r => r.json());

}

// TypeScript says this is safe

const user = await getUser(123);

console.log(user.name.toUpperCase());Runtime: The API returns { id: "123", name: null }. TypeScript’s types didn’t save you. You still need runtime validation. This is why Zod, Yup, and io-ts exist. TypeScript alone isn’t enough. You’re adding types AND validation libraries. JavaScript projects just use validation libraries.

Type definitions can be wrong. Third-party @types packages lag behind releases. You trust the types, write code TypeScript approves, then hit runtime errors because the types lied. TypeScript developers get false confidence.

The “any” escape hatch defeats the purpose. Real TypeScript codebases use “any” everywhere the type system becomes unmanageable. At that point, you’re paying the complexity tax without the safety benefit.

When TypeScript Actually Makes Sense

TypeScript isn’t always wrong. Project context determines if the trade-offs work.

Use TypeScript for large teams (10+ developers), long-lived codebases (2+ years), and library development. VS Code was built with TypeScript. Angular and NestJS target enterprise teams. If your team resembles Microsoft or Google, TypeScript makes sense.

Skip TypeScript for prototypes and MVPs. Speed matters more than type safety when validating product ideas. Startups should ship JavaScript first, add TypeScript later if the product scales.

Skip TypeScript for small teams (1-3 developers). You don’t need types when you wrote the entire codebase last week.

Skip TypeScript for simple CRUD applications. This is over-engineering for straightforward logic. Types don’t prevent bugs in SQL queries or validation rules.

The JSDoc Alternative: Types Without the Tax

Most developers don’t know JSDoc provides 80% of TypeScript’s benefits with 20% of the cost.

JSDoc adds type annotations as comments. VS Code reads these and provides autocomplete, type checking, and IntelliSense. No build step required. Write JavaScript, run JavaScript.

/**

* @param {number} id - User ID

* @returns {Promise<{id: number, name: string, email: string}>}

*/

async function getUserData(id) {

return fetch(`/api/users/${id}`).then(r => r.json());

}VS Code highlights type mismatches. Autocomplete works. Refactoring tools understand types. You get developer experience benefits without tsconfig.json, build tools, or type definitions.

JSDoc isn’t as powerful as TypeScript. Advanced features like conditional types don’t exist. For most projects, you don’t need those features. The 80/20 rule applies.

Question the Cargo Cult

The “use TypeScript for everything” default is cargo cult engineering. Teams adopt TypeScript because everyone else does. React tutorials use TypeScript. Angular requires it. Job postings list it as required. The pressure to conform is intense.

This is how teams end up with TypeScript in projects that don’t benefit. A three-person startup building an MVP doesn’t need TypeScript. They need to ship fast and iterate. TypeScript slows this down.

Tool adoption should be intentional. Ask: Does our project benefit from compile-time type checking? Do we have the team size to justify shared type definitions? Will we maintain this codebase long enough for refactoring confidence to matter?

If the answers are no, skip TypeScript. Build in JavaScript. Add JSDoc types for lightweight IDE support. Save your complexity budget for actual problems.

The Pragmatic Path Forward

TypeScript has real benefits. Large teams, long-lived codebases, and complex domains justify the investment. VS Code proves TypeScript works at enterprise scale.

TypeScript also has real costs. Build complexity, configuration overhead, velocity taxes, and false security matter. These costs exceed benefits for most projects.

The pragmatic approach: Default to JavaScript. Add JSDoc types for IDE support. Use runtime validation libraries for external data. Reserve TypeScript for projects that genuinely benefit—large teams, long lifespans, complex domains.

Don’t adopt TypeScript because “everyone uses TypeScript.” Adopt it when your project’s needs justify its costs. Most projects don’t meet that bar.

Choose your tools intentionally. Question the defaults. Build for your project’s context, not for cargo cult compliance.