David Heinemeier Hansson removed TypeScript from Turbo and Hey, called it “not worth the complexity tax,” and the JavaScript community erupted. An 847-comment Hacker News thread split nearly 50/50 between “finally someone said it” and “DHH doesn’t understand TypeScript.” The debate isn’t new, but DHH’s credibility as Ruby on Rails creator forced an uncomfortable question the industry has avoided: Are we serving the type checker or solving actual problems?

TypeScript promised to make JavaScript scale. It delivered on that promise for a while. Then it kept going. Basic type annotations evolved into conditional types, mapped types, template literal types, and recursive type utilities that rival Haskell’s complexity. What started as “JavaScript with types” became an elaborate type system that many developers spend more time fighting than benefiting from. The industry overcorrected from “no types” to “all the types,” and TypeScript’s advanced features have become type theater—impressive demonstrations that rarely prevent actual bugs.

The Complexity Escalation Nobody Asked For

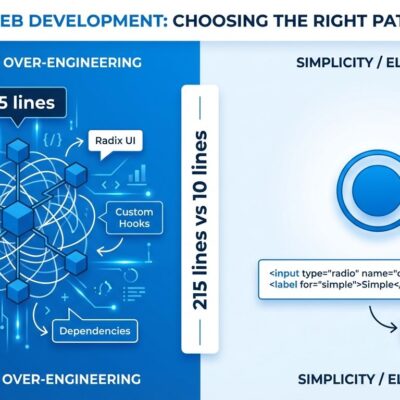

TypeScript 1.0 introduced basic type annotations: string, number, boolean, interfaces. That was 2014. It solved real problems. Fast forward to 2025, and TypeScript includes features like this:

type UnionToIntersection<U> =

(U extends any ? (k: U) => void : never) extends

((k: infer I) => void) ? I : never;How many developers actually understand that? More importantly, how many projects genuinely need it? The answer to the first question is “very few.” The answer to the second is “almost none.” But developers write utilities like this anyway because TypeScript makes it possible, the community celebrates type gymnastics as sophistication, and nobody wants to admit they don’t understand the 10-line type utility someone contributed to the codebase.

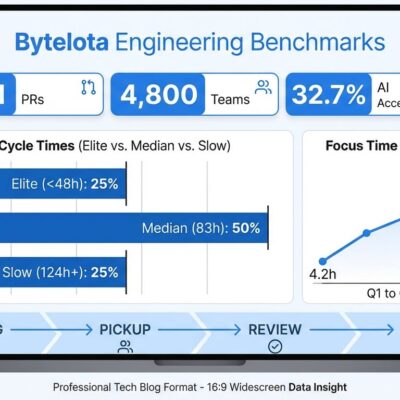

The learning curve tells the story. Developers report 2-6 months to feel proficient with TypeScript’s advanced features. That’s months spent learning a type system instead of shipping features, solving problems, or understanding the domain. When a tool’s advanced features require months of study but rarely catch bugs that simple tests wouldn’t find, that’s not a feature—that’s a complexity tax.

If you need a 10-line type utility to make TypeScript accept your valid code, the problem isn’t your code. It’s TypeScript.

Types Compile Away. The Runtime Doesn’t Care.

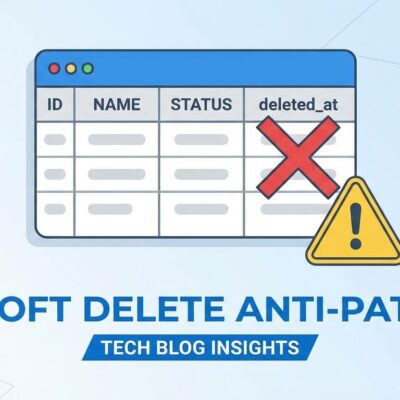

Here’s the uncomfortable truth about TypeScript: types disappear at compile time. Runtime errors still happen. “It compiles” doesn’t mean “it works.” Type safety is theater when it validates structure but not correctness.

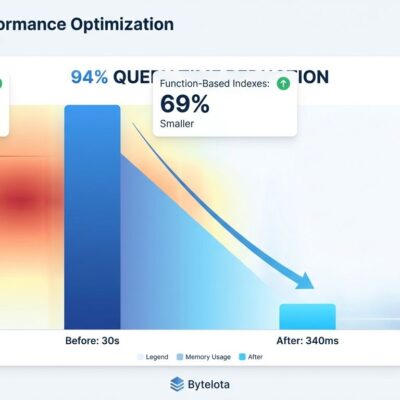

Real-world example: An e-commerce company adopted TypeScript for “safety.” Six months later, compile times hit 90 seconds, blocking hot reload. Type errors forced any escapes throughout the codebase just to make valid code compile. The kicker? Runtime bugs occurred at the same rate as before TypeScript. They got slower development and the same bug count. That’s not safety—that’s complexity for complexity’s sake.

Types catch structural errors. They don’t prevent logical bugs. A function can have perfect types while implementing the wrong algorithm. TypeScript says ✓ all good. Tests say ✗ logic is broken. Runtime says ✗ wrong result. The types gave false confidence.

Developers who lean heavily on TypeScript start trusting “it passed type check” too much. They write fewer tests because the types feel like safety. Then production hits, the types have compiled away, and the logical bugs that types never caught start surfacing. Runtime validation libraries like Zod exist specifically because types alone don’t provide real safety at the boundaries where errors actually occur.

Where TypeScript Actually Helps (And Where It Doesn’t)

TypeScript isn’t universally bad. It has legitimate use cases. The problem is most projects aren’t those use cases.

TypeScript genuinely helps large codebases with 100,000+ lines and multiple teams. Visual Studio Code is written in TypeScript for good reason—refactoring that much code without type safety would be risky. Public libraries benefit because type definitions make the consumer experience better. Complex domain logic in financial or medical systems benefits from type constraints that prevent categories of errors. Large teams use types as communication and documentation.

But small startups moving fast? TypeScript slows iteration. Prototypes where requirements change daily? Types become a maintenance burden that fights every pivot. Content sites and simple CRUD apps with limited logic complexity? Type errors are unlikely to cause issues worth the overhead. Solo projects where you wrote the code and understand it? Types add little value.

The real problem is cargo-culting. TypeScript became a checkbox, not a choice. Developers use it because “everyone uses it,” not because their specific project benefits. Job postings require TypeScript experience whether the role involves large codebases or small utilities. Ecosystem pressure forces adoption even when it actively harms the project. That’s orthodoxy, not engineering judgment.

Related: AI Copilots Are Making Developers Worse Programmers

The Pragmatic Middle Ground

You don’t have to choose between “all TypeScript” and “no types.” Pragmatic alternatives exist that most teams ignore because the industry stopped talking about them.

JSDoc provides type checking without compilation. You write type annotations in comments, get IntelliSense in your editor, and optionally run TypeScript’s checker without the build step. It’s types without the tax. Runtime validation with Zod or Yup catches errors at boundaries where they actually matter—API responses, user input, external data. That’s real safety, not type theater.

DHH’s approach after removing TypeScript: good tests, clear documentation, simpler code. The result? Faster development, fewer false-positive errors, same reliability. Tests validate behavior. Documentation explains intent. Simple code is easier to understand than complex code with elaborate types.

Decision framework: Ask yourself whether you’re building a large codebase with many contributors, a public library, or safety-critical domain logic. If yes, TypeScript might make sense. If you’re building anything else, simpler tools are probably better. The question isn’t “Should we use TypeScript?” It’s “Does this specific project justify TypeScript’s complexity?”

Challenging the Orthodoxy

The TypeScript-everywhere orthodoxy has dominated JavaScript for five years. It’s time to question it.

JavaScript had real problems. TypeScript solved them. Then it kept adding complexity beyond what most projects need. Now TypeScript’s advanced features create more problems than they solve for the majority of codebases. The pendulum swung from “no types” to “all the types.” It needs to swing back toward pragmatism.

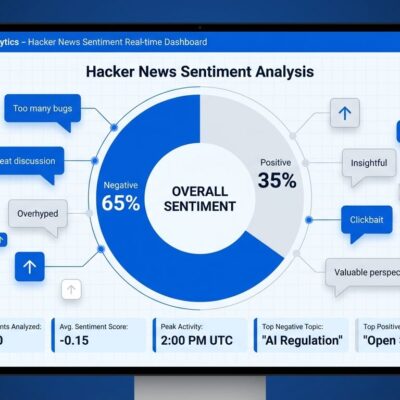

The backlash is real. DHH’s posts go viral because they articulate what many developers feel but hesitate to say publicly. Hacker News threads show 50/50 splits. Reddit sees weekly “unpopular opinion: TypeScript” threads with thousands of responses. Developers admit privately: “I use it because my job requires it, not because I want to.” Even the Svelte team considered dropping TypeScript before community pressure kept it.

One developer called TypeScript “Stockholm Syndrome for JavaScript developers.” That’s harsh, but it’s resonating. Complexity fatigue is widespread. Developers spend hours satisfying the type checker instead of solving actual problems. That’s not progress.

If you question whether your project needs TypeScript, you’re not alone. If you think simpler tools might work better, you’re probably right. If you use TypeScript because the industry says so rather than because your project benefits, that’s worth examining.

TypeScript’s advanced features don’t make you a better programmer. Sometimes they make you worse—focused on type gymnastics instead of good code, trusting compile checks instead of writing tests, serving the type checker instead of solving problems.

The uncomfortable truth: for most projects, TypeScript’s complexity trap hurts more than helps. You don’t need TypeScript for every project despite what the industry orthodoxy claims. Choose tools that serve your project, not tools that make you serve them.

Key Takeaways

- TypeScript’s advanced features create “type theater”—elaborate type gymnastics that feel like safety but rarely prevent actual bugs in production

- Types compile away at runtime, so “it compiles” doesn’t mean “it works”—logical bugs and runtime errors still happen at the same rate

- TypeScript genuinely helps large codebases (100K+ LOC), public libraries, and safety-critical systems, but most projects aren’t those use cases

- Cargo-culting drives adoption more than engineering judgment—developers use TypeScript because the industry says so, not because their project needs it

- Pragmatic alternatives exist: JSDoc for types without compilation, runtime validation for real safety, good tests and documentation for maintainability