Zig 0.16.0 previews a radical solution to async programming’s biggest problem—function coloring—with a generic Io interface that lets code run on sync threads or async event loops without modification. While JavaScript, Python, Rust, and C# force entire codebases to choose async or sync execution models, Zig’s approach treats I/O like memory allocation: functions accept an Io parameter and stay agnostic about the underlying runtime. Critics argue it relocates rather than eliminates the problem, but after a decade of high-level languages stagnating on this issue, Zig’s experimentation deserves attention.

The Function Coloring Problem, Ten Years Later

In 2015, Bob Nystrom published “What Color is Your Function?”—a devastating critique of async/await syntax. The problem is simple but viral: once you mark a function async, every function that calls it must also be async. JavaScript Promises, Python’s asyncio, Rust’s async/await, C#’s Task model—they all suffer the same infection. Write one async function and watch the async keyword propagate through your entire codebase like a dependency virus.

The pain is real and measurable. Django’s ORM still lacks comprehensive async support in 2025, forcing developers to choose between mature sync libraries or fragmented async alternatives. Rust’s async ecosystem splits between std::fs and tokio::fs. JavaScript developers write separate sync and async versions of the same library because Promises can’t call synchronous code without blocking the event loop.

Ten years after Nystrom’s critique, high-level languages haven’t solved this. They’ve just normalized the pain.

Zig’s Interface-Based Solution

Zig 0.16.0 takes a different approach: async behavior comes from calling conventions, not function declarations. Lead developer Andrew Kelley describes it simply: “Setting up a std.Io implementation is a lot like setting up an allocator.”

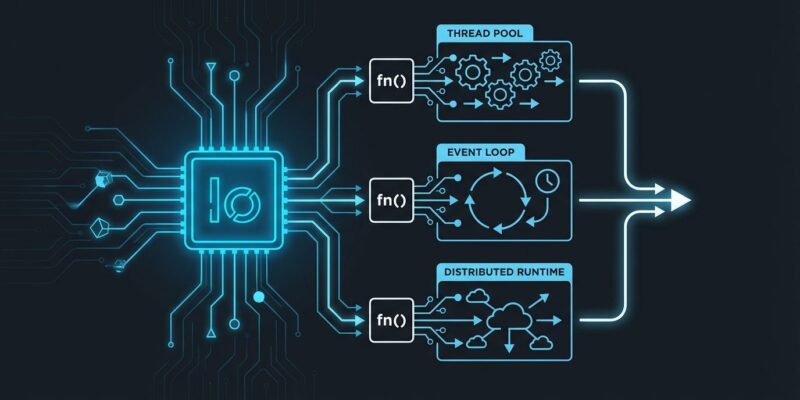

Functions accept an Io parameter and remain agnostic about execution models. The same code can run on Io.Threaded (thread pools for desktop apps), Io.Evented (event loops for web servers), or custom implementations for embedded systems. No function coloring. No viral async propagation. No ecosystem splits between sync and async library versions.

Here’s what it looks like in practice:

var future = io.async(doWork, .{io});

future.await(io);The key innovation: io is just a parameter. Swap Io.Threaded for Io.Evented and the code runs identically on different execution models. Library authors write once, application developers choose the runtime.

Asynchrony Is Not Concurrency

Zig forces a distinction most languages blur: asynchrony versus concurrency. The async() operation allows reordering but doesn’t guarantee parallelism. The concurrent() operation explicitly requests parallel execution and fails with error.ConcurrencyUnavailable if the executor can’t deliver.

This matters because unbuffered channels deadlock with async() on single-threaded executors—both producer and consumer can’t progress without true parallelism. Using concurrent() makes this requirement explicit:

var producer = try io.concurrent(producer_fn, .{io, &queue});

var consumer = try io.concurrent(consumer_fn, .{io, &queue});The code honestly declares its needs. If you run this on a single-threaded executor, you get an error, not a silent deadlock. That’s language design prioritizing correctness over convenience.

The Skepticism Is Justified

Community reaction on Hacker News (261 points, 198 comments) is cautiously optimistic at best. The core criticism: Zig relocates function coloring rather than eliminating it. Functions requiring Io parameters still create call chain constraints. You’re passing an interface instead of marking functions async, but the viral propagation remains.

It’s parameter drilling all the way down—similar to Go’s context.Context pattern. Nested functions require threading Io through every layer. Virtual function calls through the interface add runtime overhead, though proposal #23367 promises de-virtualization for monomorphic use cases.

The previous Zig async design supported suspend/resume primitives for OS kernel development. That capability is lost in the new model. For systems programmers building interrupt-driven kernels, this is a regression.

Better Trade-Offs, Not Magic Solutions

Zig’s position becomes clearer when compared to alternatives:

Rust chose zero-cost abstractions at compile time. Async functions create different types, forcing ecosystem fragmentation. The trade-off: maximum performance, minimum flexibility.

Go chose runtime overhead for every function. Goroutines work everywhere without explicit marking. The trade-off: hidden costs, maximum convenience.

JavaScript and Python chose viral async/await with no escape hatches. The trade-off: simple mental model, maximum ecosystem pain.

Zig picks runtime flexibility with explicit interfaces. The trade-off: visible parameter passing, portable code. It’s honest about costs rather than hiding them behind compiler magic or runtime overhead.

Is this better? That depends on what you’re building. For libraries targeting multiple deployment contexts—web servers, desktop apps, embedded systems—Zig’s approach eliminates duplication. For simple applications where one execution model suffices, it’s unnecessary complexity.

Production Reality Check

Before declaring victory, consider the timeline. Zig 0.16.0 is preview quality, releasing in roughly March 2026. Kelley admits the design “will probably take a few iterations to get it right.” The Io.Evented event loop implementation requires pending language features—stackful coroutines and stack size introspection—that don’t exist yet.

Current proof-of-concept is Io.Threaded, which works with thread pools but lacks the performance characteristics of event loops. And Zig still hasn’t reached 1.0 stable, leaving the language in what some community members call “perpetual early access.”

This is experimental work, not production-ready infrastructure.

Why This Matters Anyway

Function coloring has plagued async programming for ten years. JavaScript, Python, Rust, and C# all normalized the pain without solving it. Zig’s approach—interface-based async with explicit execution models—represents genuine language innovation where high-level languages stagnated.

Does it truly solve function coloring? No—it relocates the constraint to parameter passing. But that’s a more honest trade-off than compiler magic (Rust) or hidden overhead (Go). Systems programming needs options beyond “zero-cost but inflexible” and “convenient but expensive.”

The design avoids catastrophic flaws even if it doesn’t achieve perfection. For a systems language still finding its identity, that’s worth watching.