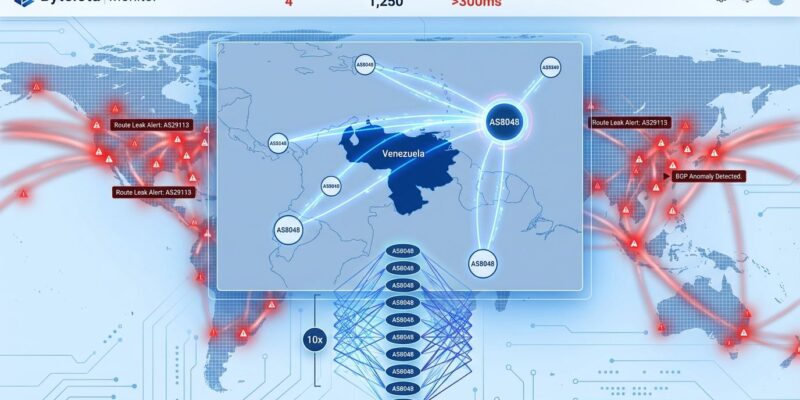

On January 2-6, 2026, during a major power blackout in Caracas, Venezuela, network monitoring systems detected bizarre BGP routing anomalies affecting CANTV (AS8048), the country’s state-owned telecom. Cloudflare Radar flagged 8 IP prefixes being routed through abnormal paths with CANTV’s autonomous system number appearing 10 times in the AS path—a configuration so unusual it deliberately repels traffic. The affected address blocks belonged to Dayco Telecom, a Caracas hosting provider serving critical infrastructure including banks, ISPs, and email servers. The timing coincided with US military operations and widespread internet outages, sparking debate: infrastructure failure, network manipulation, or coincidence?

The Prepending Paradox: Why 10x Makes No Sense for an Attack

Here’s the technical smoking gun: CANTV’s autonomous system number (AS8048) appeared repeated 10 times in the AS path for the affected routes. In BGP routing, AS path prepending is a traffic engineering technique where networks add their ASN multiple times to make routes appear longer and less attractive. BGP prefers shorter paths (fewer hops = faster routing), so prepending actively discourages traffic from using that route.

Network engineers consider 1-3 prepends normal for load balancing, 5+ unusual, and 10+ excessive to the point of misconfiguration. The IETF standards on AS path prepending recommend limiting prepends to 1-3 times. If someone wanted to hijack traffic, they’d announce clean, short AS paths to attract traffic. The 10x prepending does the opposite—it’s a terrible hijack if it’s a hijack at all.

According to the network engineering community on Hacker News (758 points, 337 comments), this points to accidental misconfiguration rather than sophisticated attack: “Looking at CANTV’s announcements from outside that period shows they do this a lot.” The 10x prepending appears to be CANTV’s normal, if excessive, practice for traffic engineering—not a one-time attack pattern.

Banks, ISPs, Email: Critical Infrastructure Goes Dark

The 8 affected IP prefixes (200.74.226.0/24 through 200.74.238.0/23) all fall within a block belonging to Dayco Telecom (AS21980), a Caracas-based hosting provider operating the only geo-distributed multisite data center infrastructure in Venezuela. WHOIS lookups confirmed ownership, while reverse DNS revealed these address ranges host banks, internet service providers, and email servers serving Venezuela’s capital.

Dayco operates a TIER III certified data center in Caracas—the first in Venezuela to achieve that designation—with a 1,000 m² technical facility running at 85% occupancy. When its prefixes leaked through CANTV’s misconfigured routing, critical services went offline during a 12+ hour window between the BGP anomaly detection (January 2, 15:40 UTC) and military operations (January 3, ~06:00 UTC). The sensitivity of the affected infrastructure is why this incident gained attention beyond technical curiosity.

Whether accidental or intentional, this demonstrates the vulnerability of centralized infrastructure in geopolitically unstable regions. Internet routing can become collateral damage during conflicts, even without malicious intent.

Network Engineers Call It: Accident, Not Attack

The Hacker News discussion (337 comments from network engineers) reached a clear consensus: likely accidental misconfiguration. The most credible technical explanation came from an experienced operator: “CANTV had too loose of a routing export policy facing their upstream AS52320 neighbor, and accidentally redistributed the Dayco prefixes when direct routes became unavailable. This is a pretty common mistake.”

BGP route leaks happen during infrastructure outages. Power failure triggers routing instability, misconfigurations activate, and suddenly your internal routes leak to the internet. The fact that CANTV routinely uses 10x prepending for traffic engineering—combined with loose export filters during infrastructure chaos—makes the boring explanation more plausible than the exciting conspiracy theory.

The anomaly appeared 12+ hours before military operations, suggesting unrelated infrastructure damage rather than coordinated cyber warfare. As one engineer noted: “If this was a hijack, it’s a terrible hijack. The 10x prepending makes routes less attractive.” The technical evidence supports incompetence over malice.

How Cloudflare Radar Caught This (And How You Can Too)

Cloudflare Radar automatically detected the Venezuela route leak on January 2 at 15:40 UTC using its multi-source BGP monitoring system. The service ingests data from CAIDA, UCSD, IHR, and Cloudflare’s own global network, examines each route for provider-customer-provider leak patterns, and aggregates individual anomalies into route-leak events. This detection happened before widespread public awareness of the blackout.

Historically, BGP monitoring required network engineering expertise and expensive tools. Cloudflare Radar democratizes this—any developer can monitor BGP for their infrastructure using free, public tools accessible at radar.cloudflare.com/routing. The service offers API access and can send alerts via email or PagerDuty for monitored prefixes. For developers running internet services, this is actionable: you can monitor BGP even if you’re not a network engineer.

BGP Incidents Happen Daily—This One Just Had Timing

BGP incidents aren’t rare. Since 2020, there have been over 1,430 BGP hijacking incidents globally, averaging 14 hijackings per day. Venezuela’s incident is relatively small (8 prefixes vs thousands in major incidents like the 2020 hijack affecting 8,800+ prefixes across Akamai, Amazon, and Alibaba). Historical examples include the 2008 YouTube outage (Pakistani ISP accidentally blocked YouTube globally), 2018 cryptocurrency theft ($152K stolen via Route53 hijack), and 2024 Cloudflare 1.1.1.1 outage (BGP hijack took down popular DNS resolver).

BGP was designed in 1989 assuming trustworthy operators—no built-in authentication or validation. Modern mitigations like RPKI (cryptographic signing) exist but adoption is slow (~40% coverage globally). The Venezuela case is notable for its geopolitical context and unusual technical details (10x prepending), but it’s part of a larger pattern. BGP vulnerabilities affect everyone on the internet, not just network operators.

The technical evidence strongly favors accident over attack: 10x prepending repels traffic, CANTV has a history of excessive prepending, and route leaks are common during infrastructure failures. But the lesson remains: internet routing can fail catastrophically during geopolitical crises, whether or not there’s malicious intent. For developers building resilient systems, external BGP monitoring should be on your radar—literally.