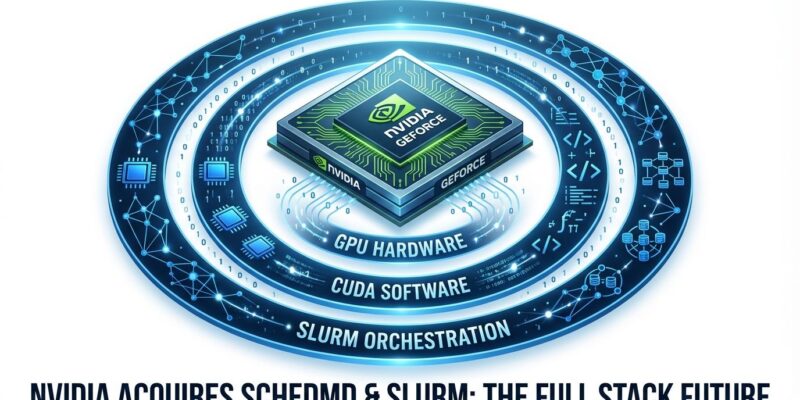

Nvidia announced on December 15, 2025, that it’s acquiring SchedMD, the primary commercial developer of Slurm—the open-source workload management system powering approximately 65% of the world’s TOP500 supercomputers. This completes Nvidia’s vertical integration of the AI infrastructure stack, giving the company control over hardware (GPUs), software (CUDA), and now orchestration (Slurm). While Nvidia promises to keep Slurm open-source and vendor-neutral, the move gives it unprecedented influence over how AI workloads get scheduled and managed at massive scale.

If you’re running GPU clusters for AI training, this affects you. Nvidia now controls the full compute stack—from the chips themselves to the software that decides when and how those chips get used. Industry analysts warn of potential “soft lock-in” through performance optimizations favoring Nvidia’s ecosystem, even if Slurm remains technically open-source.

Nvidia Completes the Stack: Hardware, Software, Orchestration

Nvidia’s acquisition of SchedMD gives the company end-to-end control over AI infrastructure. It already dominated GPUs (A100, H100, Blackwell) and created a moat with CUDA and its vast ecosystem of optimized libraries. Now it owns the orchestration layer through Slurm, which manages workloads on more than half of the top 10 and top 100 systems on the TOP500 list.

This mirrors the strategy of cloud giants like AWS, Google, and Azure, which own their full stacks from hardware to orchestration. However, Nvidia is doing this for on-premises and private cloud infrastructure—the domain where enterprises and research institutions run their largest AI training workloads.

Industry analysts didn’t mince words. The Next Platform called it Nvidia “nearly completing its control freakery,” noting that the company has been making moves designed to deepen platform-level lock-in even as hardware alternatives emerge.

What Is Slurm and Why It Matters

If you’ve never heard of Slurm (Simple Linux Utility for Resource Management), you’re not alone—it operates behind the scenes. However, if you’ve trained a large language model, run scientific simulations, or used a university research cluster, there’s a good chance Slurm was orchestrating those workloads.

Originally launched in 2002 by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory and collaborators, Slurm handles job scheduling, resource allocation, and queue management for clusters ranging from hundreds to tens of thousands of nodes. SchedMD, founded in 2010 by Slurm’s original creators Morris Jette and Danny Auble, serves hundreds of customers including cloud providers, AI companies, research labs, and government agencies across industries like autonomous driving, healthcare, energy, and finance.

SchedMD CEO Danny Auble called the acquisition “the ultimate validation of Slurm’s critical role in the world’s most demanding HPC and AI environments.”

Open Source Promises Meet Vendor Lock-in Concerns

Nvidia’s official stance is reassuring: “NVIDIA will continue to develop and distribute Slurm as open-source, vendor-neutral software, making it widely available to and supported by the broader HPC and AI community across diverse hardware and software environments.”

Nevertheless, analysts are skeptical. Network World noted that “the acquisition signals a push toward co-design between GPU scheduling and fabric behavior,” predicting that Nvidia will steer development toward tighter integration with its own communication libraries (NCCL), networking fabrics (InfiniBand, RoCE), and GPU architectures. The Next Platform went further, warning that just because Slurm remains open-source doesn’t mean Nvidia will support the open version or make all future features available to the community.

This is the classic open-source dilemma: a project can remain technically open while being subtly guided toward one vendor’s ecosystem. Organizations using AMD or Intel GPUs may find future Slurm optimizations don’t benefit their hardware as much, creating “soft lock-in” through performance gaps rather than hard technical barriers.

What Developers and Organizations Should Know

For those using Slurm today, the acquisition brings both opportunities and risks. On the positive side, expect tighter CUDA integration, better support for Multi-Instance GPU partitioning, and optimizations for Nvidia’s upcoming Blackwell architecture and future GPUs. Development velocity will likely accelerate given Nvidia’s resources.

On the negative side, organizations running multi-vendor GPU environments should watch closely. Will future Slurm features prioritize Nvidia hardware? Could performance optimizations create gaps for non-Nvidia GPUs? These questions matter for infrastructure planning.

Alternative orchestration options exist for those concerned about vendor alignment. Kubernetes offers better support for dynamic workloads, inference services, and auto-scaling, though it lacks Slurm’s sophisticated batch scheduling. Meanwhile, many organizations run hybrid setups—Slurm for training, Kubernetes for inference. PBS Pro remains an open-source alternative with a smaller community, while Ray is emerging as a framework for distributed AI workloads.

The Bigger Picture: Infrastructure Consolidation

Nvidia’s SchedMD acquisition fits a broader pattern of AI infrastructure consolidation. Cloud providers have long controlled their full stacks, and Nvidia is now replicating this for on-premises AI infrastructure. Furthermore, the company’s 10+ year collaboration with SchedMD has been formalized, completing its vertical integration from silicon to scheduling.

This level of consolidation has benefits—tighter integration, better optimization, accelerated innovation. Conversely, it also concentrates power, potentially reducing competition and developer choice. The question isn’t whether Nvidia will maintain Slurm as open-source (it will), but whether that open-source project remains genuinely vendor-neutral or becomes subtly optimized for Nvidia’s ecosystem.

For developers, the takeaway is clear: Nvidia now influences every layer of the AI infrastructure stack for GPU-accelerated computing. Whether that’s a feature or a bug depends on your perspective—and your hardware choices.