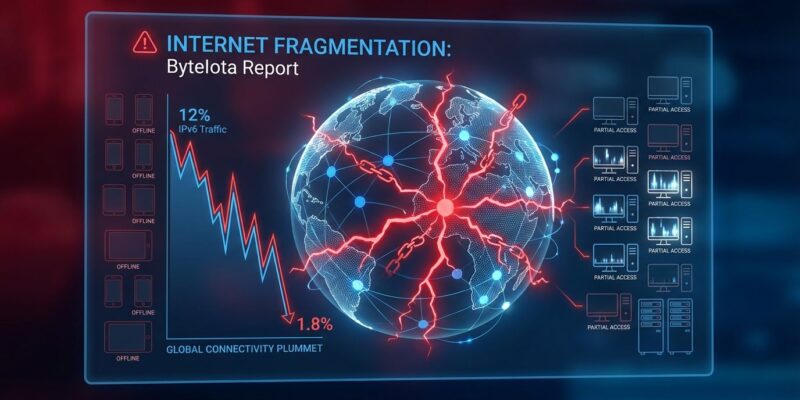

Yesterday, on January 8, 2026, at 12:00 UTC, Iran executed the first large-scale IPv6-specific internet blackout. Cloudflare Radar detected Iran’s IPv6 address space dropping 98.5%—from 12% to 1.8% traffic share—in a calculated attack that killed mobile internet while keeping desktop connections partially alive. This isn’t just another censorship story. It’s a precedent that exposes a fundamental vulnerability in how we’ve built the modern internet.

Why IPv6 Creates a New Censorship Attack Surface

Mobile networks run primarily on IPv6. Desktop broadband still uses legacy IPv4. Iran’s government understands how to surgically censor IPv4 traffic at their national gateway—the Telecommunication Infrastructure Company (TIC)—because IPv4 filtering is well-established. But IPv6 is too complex for selective filtering. Their solution? Block it entirely.

A developer on Hacker News captured the asymmetry: “They can censor IPv4 when they want, but they don’t know how to censor IPv6. So they block it entirely.” When mobile carriers transitioned from 3G to 4G, they adopted IPv6 for VoIP and direct connectivity advantages. That architectural choice now creates a protocol-specific kill switch. Block IPv6, and mobile internet dies. Keep IPv4 running, and desktop users stay partially online.

This is the trade-off the industry didn’t talk about: IPv6 is more efficient, but its complexity makes wholesale blocking easier than granular censorship. “Better protocol, worse censorship resistance” isn’t a feature anyone advertised.

Engineered Degradation Beats Full Blackouts

Iran didn’t disconnect from the global internet like Egypt did in 2011. That five-day shutdown was politically disastrous and drew international condemnation. Instead, Iran uses what researchers call “engineered degradation“—layered disruptions that render the internet unusable without triggering full-shutdown optics.

The technical implementation is sophisticated: bandwidth throttling (traffic down 35% since early January), DNS manipulation (fake private IPs instead of real addresses), protocol whitelisting (only DNS, HTTP, and HTTPS forwarded), and deep packet inspection for keyword filtering. The result? Packet loss exceeding 30%, jitter spikes making connections unreliable, and international bandwidth so constrained that external access is effectively dead.

IranWire’s analysis notes that “rather than shut down networks, which would draw attention and controversy, the government was rumored to have slowed connection speeds to rates that would render the Internet nearly unusable.” This pattern has repeated since the 2009 presidential election, through the 2013 election cycle, and now during the 2025-2026 economic protests triggered by the Rial collapsing to 1.5 million per USD.

The strategy works because it’s sustainable. You can run engineered degradation for weeks. It’s harder to document than a full blackout, politically safer, and provides plausible deniability. It’s the blueprint other authoritarian regimes will follow.

The Single Gateway Kill Switch

All Iranian internet traffic routes through one centralized chokepoint: the TIC. This architectural reality creates a catastrophic single point of censorship failure. No protocol upgrade—not IPv6, not encrypted DNS, not Tor—can solve a political problem rooted in physical infrastructure control.

Comparisons to other regimes are instructive. China filters both IPv4 and IPv6 at scale using deep packet inspection. Russia exercises systematic router port control and gradual disconnection. Egypt went for full BGP withdrawal in 2011 but paid the political price. Iran’s approach is more subtle: selective IPv6 blocking gives them granular control without the blowback.

The Hacker News thread is filled with developers debating workarounds, and the consensus is bleak. Starlink? Only 0.1% population penetration, requires smuggling hardware, and financially inaccessible to most. VPNs and Tor? Blocked by DPI during unrest. Mesh networks like Yggdrasil? Need existing connectivity to bootstrap, which makes them useless during blackouts. One commenter’s assessment cuts through the technical optimism: “Centralized gateways are single points of censorship failure, and no protocol upgrade alone solves political suppression without distributed architecture redesign.”

Iran has adapted to this reality by building a nation-wide intranet for domestic services. Critical systems like payment infrastructure function offline, decoupled from the global internet. When protest suppression requires it, they can isolate citizens without breaking their own economy.

What Developers Need to Know

This is the first documented large-scale IPv6-specific blackout. Before yesterday, governments shut down all internet or filtered all protocols. Now they can selectively kill mobile connectivity while keeping desktop access partially operational. That’s a new capability, and other regimes are paying attention.

The implications are practical. If you’re building mobile-first applications, you now have a protocol-specific censorship vulnerability that didn’t exist—or wasn’t exploitable—under IPv4-dominant infrastructure. Dual-stack deployment isn’t just a best practice anymore; it’s a political necessity. IPv6-only services are easier to block than dual-stack architectures, especially in countries with less sophisticated filtering infrastructure.

The assumption that “IPv6 is just a better version of IPv4” ignores geopolitical reality. IPv6’s efficiency comes with a censorship cost: its complexity prevents selective filtering, which makes wholesale blocking the path of least resistance for governments without China-level DPI capabilities. Protocol designers optimized for performance and scalability. They didn’t optimize for authoritarian resilience.

As of this writing, Iran’s IPv6 remains down. The protests continue—now in their 12th day—with at least 36 people killed and more than 2,000 detained. NetBlocks reports some regions at 4% connectivity. The economic crisis that triggered the unrest hasn’t resolved, which means this blackout could run for weeks.

The precedent is set. Other countries will replicate Iran’s strategy because it works. Developers building global infrastructure need to account for protocol-level censorship as a design constraint, not an edge case. Centralized gateways create kill switches. IPv6 adoption creates new attack surfaces. And no amount of clever engineering will change the fact that authoritarian governments control physical infrastructure.