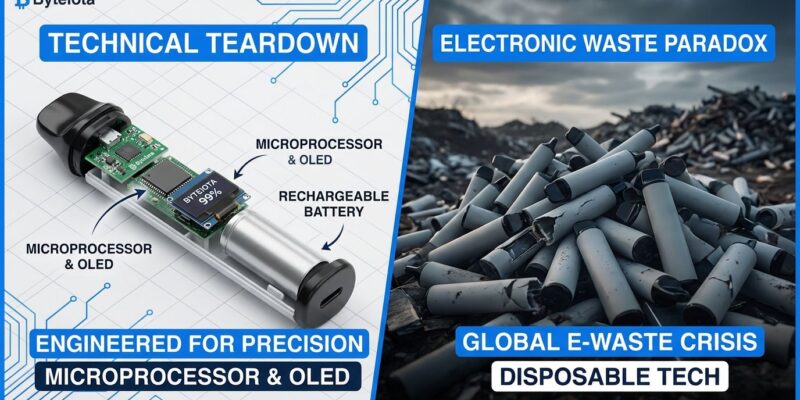

Cloudflare CTO John Graham-Cumming tore down a Fizzy Max III disposable vape and found something that should make every engineer uncomfortable: dual circuit boards, an 800mAh rechargeable battery with USB-C charging, three microphones, an OLED display, and a dedicated microprocessor. All of it engineered to be thrown away after 60,000 puffs.

The story is trending #1 on Hacker News with 481 points and 413 comments, and for good reason. This isn’t about vaping – it’s about what we’re optimizing for as an industry.

The Teardown: More Sophisticated Than You’d Expect

Graham-Cumming’s detailed teardown reveals a device that rivals many IoT products in complexity. The Fizzy Max III contains two separate circuit boards managing three heating element pairs, each with its own transistor control. Three microphones detect suction in six different positions, enabling flavor combinations by selectively activating different chambers.

The device includes an OLED display showing real-time battery percentage and liquid levels, all powered by an 800mAh lithium-polymer battery charged via USB-C. There’s even a microprocessor with debug pads – though Graham-Cumming couldn’t crack it, suggesting intentional IP protection.

For context, dual mesh coils require 20-30W power management. That’s real engineering: thermal control, power optimization, sensor fusion, and user interface design – all miniaturized into a pocket-sized form factor retailing for $15-25.

But Here’s the Strange Part

It’s rechargeable. It has USB-C. The battery could last years. The display actively encourages you to monitor battery life and recharge. Yet after 60,000 puffs – maybe a few months of use – you’re supposed to throw away the battery, both circuit boards, the display, the microprocessor, and all that engineering effort.

As Graham-Cumming puts it: “After 60,000 puffs users are meant to throw away a battery, display, microprocessor etc. …it’s a crazy large amount of technology for nicotine.”

This is planned obsolescence weaponized. Not software updates slowing down your phone, but disposable hardware sophisticated enough to last yet designed not to.

Market Forces Don’t Care About Waste

This isn’t an accident – it’s market incentives working exactly as designed. The disposable vape market grew from $7.25 billion in 2025 to a projected $16.7 billion by 2033. Competition drives innovation: 20,000-puff devices are now standard, with premium models hitting 50,000-60,000 puffs.

Features once exclusive to premium reusable pod systems – adjustable wattage, airflow control, boost modes, displays – have migrated to disposables. Consumers want convenience and performance, and manufacturing scale in China delivers both at price points that make replacement cheaper than maintenance.

The market rewards throwing away working tech, so that’s what we build.

The E-Waste Question Engineers Can’t Ignore

Electronic waste is the fastest-growing waste stream globally, with only 17.4% properly recycled. Disposable vapes add batteries, circuit boards, displays, microprocessors, and nicotine residue to landfills at scale. One Hacker News commenter summarized it: “The e-waste involved in that sub-industry must be absolutely horrifying.”

Research on engineers’ responsibility for e-waste emphasizes considering disadvantaged stakeholders – like workers in developing nations who informally recycle electronics through open burning and acid baths. That’s where much of this sophisticated tech eventually ends up.

ByteIota recently covered wearable e-waste (PCBs are 70% of the problem), but disposable vapes raise a sharper question: Should we design throwaway high-tech products at all? Is miniaturization talent being applied to solve the right problems?

What This Reveals About Consumer Electronics

Disposable vapes are a microcosm of the broader industry. Smartphones get harder to repair while miniaturization and system-on-chip technology advances. Smartwatches become obsolete when batteries degrade. Earbuds last 18 months before hitting landfills. We keep making things smaller, smarter, and more disposable.

The engineering achievement in a $20 disposable vape – dual boards, microphone arrays, power management, display integration – is genuinely impressive. So is the cost optimization that makes it economically viable. But impressive engineering in service of disposability at scale isn’t something to celebrate uncritically.

The Hacker News community sees silver linings: repurposing those 800mAh batteries, salvaging displays, hosting websites on vape hardware (yes, someone did that). But most devices will never be hacked or repurposed. They’ll just end up in the waste stream.

For developers and engineers reading this: disposable vapes force a question about how we apply our skills. Market forces reward innovation, miniaturization, and cost optimization. But should every technical problem be solved by building more sophisticated things designed to be thrown away?

There’s no easy answer, but Graham-Cumming’s teardown makes one thing clear: we’re really good at building complex things. Maybe it’s time to think harder about whether we should.