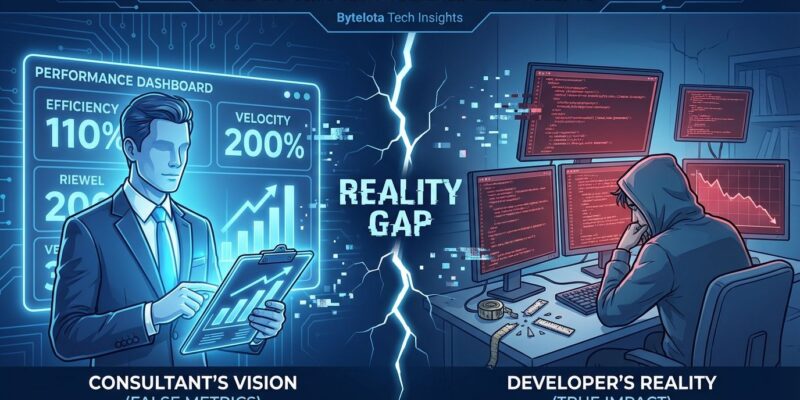

McKinsey said “Yes, you can measure software developer productivity.” The engineering community said “No, you can’t—and you’re making it worse.” When the consulting giant published its developer productivity measurement framework in August 2023, engineering leaders immediately pushed back. The problem: four of McKinsey’s five metrics measure effort and output—code volume, activity levels, deployment frequency—rather than outcomes and impact. Customer value and business results get ignored in favor of easily quantifiable proxies that developers can game.

The stakes couldn’t be higher. How developers are measured determines how they’re managed, compensated, and evaluated. Flawed metrics lead to gaming behavior, burnout, and worse software quality. Yet companies keep chasing measurement systems that engineering reality refuses to accommodate.

Measuring Effort Instead of Outcomes

Gergely Orosz of The Pragmatic Engineer and Kent Beck immediately identified McKinsey’s fundamental error: measuring earlier in the effort-output-outcome-impact cycle creates perverse incentives. As they argued, “Four of McKinsey’s five new metrics measure effort or output, which customers, executives, and investors don’t actually care about.” When measurement focuses on code volume instead of customer value, developers optimize for the wrong proxy.

The Hacker News community response was swift and unanimous. One developer nailed it: “McKinsey’s report targets C-level decision makers lacking technical understanding, trading uncertainty for meaningless numbers.” Another called out “management-consultant thinking that expects constant typing rather than problem-solving.” Even former finance developers mocked the approach as absurd. The divide between consulting theory and engineering reality couldn’t be clearer.

McKinsey’s influence makes this dangerous. When a prestigious consulting firm validates metric-driven management, executives adopt it—despite engineering leaders explaining why it fails. Consequently, developers end up measured by proxies that harm actual productivity.

Developers Are 19% Slower with AI (But Think They’re Faster)

A July 2025 study by METR exposed an even more troubling reality: we can’t even accurately perceive our own productivity changes. The randomized controlled trial tested 16 experienced open-source developers—from projects averaging 22,000+ GitHub stars—on 246 real repository issues. Half used AI coding tools (Cursor Pro with Claude), half didn’t. Result: developers with AI completed tasks 19% slower than those without.

The most striking finding: despite measuring slower, developers believed AI improved their speed by 20% post-study. This perception-reality gap reveals how broken software engineering metrics have become. If experienced developers can’t accurately assess their own productivity, how can managers measure it externally?

Related: AI Productivity Paradox: Think 20% Faster, Actually 19% Slower

Meanwhile, the industry claims dramatic productivity gains: 76% more code written, 21% more tasks completed, 55% faster completion. Yet organizational delivery metrics stay flat—the “AI productivity paradox.” Activity increases while outcomes stagnate. What looks like productivity may actually be slower delivery wrapped in inflated activity metrics.

Lines of Code and Story Points: Actively Harmful

The software engineering industry has reached universal consensus: lines of code, story points, and commit counts aren’t just ineffective—they’re actively harmful. These metrics create the exact wrong incentives.

Consider lines of code. The best engineering work often reduces code through refactoring and simplification. A junior developer generates 1,000 lines of AI-assisted boilerplate—looks productive on paper. A senior developer refactors 500 lines into 200 lines of cleaner, more maintainable code—registers as “negative productivity.” The metric inverts reality. As one industry analysis put it: “Lines of code are not just ineffective, but actively harmful. They incentivize verbose, inefficient code and punish the most valuable engineering work.”

Story points and velocity face similar problems. Originally designed for internal team planning, they’ve been corrupted into performance metrics and cross-team comparisons. The result: developers inflate estimates to hit velocity targets, managers compare teams with completely different contexts, and trust erodes. When velocity determines evaluations, gaming becomes rational behavior.

Facebook learned this lesson the hard way. Survey scores initially provided valuable feedback for improvement. However, once rolled into performance reviews and management hierarchies, corruption followed. Managers traded evaluation scores for higher metrics. Directors cut teams based purely on declining numbers—regardless of business impact. The measurement act itself changed behavior, usually for the worse.

When Measurement Becomes the Target

Goodhart’s Law states: “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.” Facebook’s experience proves the pattern. Companies introduce metrics to improve productivity. Metrics show progress. Executives tie metrics to performance evaluations. Developers game the metrics. Metrics become useless. Companies introduce new metrics. The cycle repeats.

This isn’t theoretical speculation—it’s documented reality at one of the world’s top tech companies. The fundamental problem: measurement changes developer behavior. Tie metrics to evaluations, and gaming becomes inevitable. Moreover, focusing on easily quantifiable proxies leads developers to optimize for those proxies instead of genuine productivity.

The consulting industry sells measurement systems to executives who want simple answers to complex questions. Nevertheless, software development is creative knowledge work, not factory assembly. Traditional productivity metrics from manufacturing don’t translate to code. The things easiest to measure—code volume, commits, hours logged—are often inverse indicators of actual productivity.

What Actually Works Instead

The engineering community has better alternatives. The SPACE framework, created by Nicole Forsgren at Google, Microsoft Research, and GitHub, provides multi-dimensional measurement: Satisfaction, Performance, Activity, Communication, and Efficiency. Unlike narrow output metrics, SPACE balances technical and human factors.

The key difference: measure team effectiveness, not individual output. Track customer-facing features shipped weekly. Monitor business impact commitments teams make. Furthermore, protect focus time—2025 benchmarks show median developers get 4.2 hours of uninterrupted work daily, while elite teams protect 7.2+ hours. Ask “what’s blocking us?” instead of “why are you slow?”

Orosz and Beck recommend measuring like sales teams measure results: track outcomes, not outputs. Sales teams succeed because they’re measured on deals closed and revenue generated—results customers care about. Engineering should follow the same principle. Did we ship features that solve customer problems? Did we move business metrics? Did we reduce production incidents? These outcomes matter. Lines of code don’t.

Use metrics for diagnosis, never for evaluation. When metrics inform process improvements rather than performance reviews, gaming incentives disappear. Teams can honestly assess bottlenecks and experiment with solutions. But the moment metrics determine bonuses or promotions, the corruption cycle begins.

Key Takeaways

- McKinsey’s framework measures effort and output instead of outcomes and impact—engineering leaders universally rejected this approach because it creates perverse incentives that harm actual productivity.

- The METR study exposed a critical gap: developers with AI tools were 19% slower yet believed they were 20% faster, proving we can’t even accurately perceive our own productivity changes.

- Lines of code, story points, and commit counts are actively harmful metrics that incentivize gaming behavior, punish valuable engineering work like refactoring, and invert productivity reality.

- Use the SPACE framework to measure team effectiveness across five dimensions—Satisfaction, Performance, Activity, Communication, Efficiency—instead of individual output metrics.

- Measure outcomes (features shipped, customer value delivered, business impact) not outputs (code volume, commits, activity), and use metrics for diagnosis rather than evaluation to avoid the corruption cycle.

Developers should resist metric-driven management and educate leaders on why measurement as currently practiced fails. The consulting industry may sell simple answers, but software development demands better understanding. Focus on delivering value, not optimizing proxies.